|

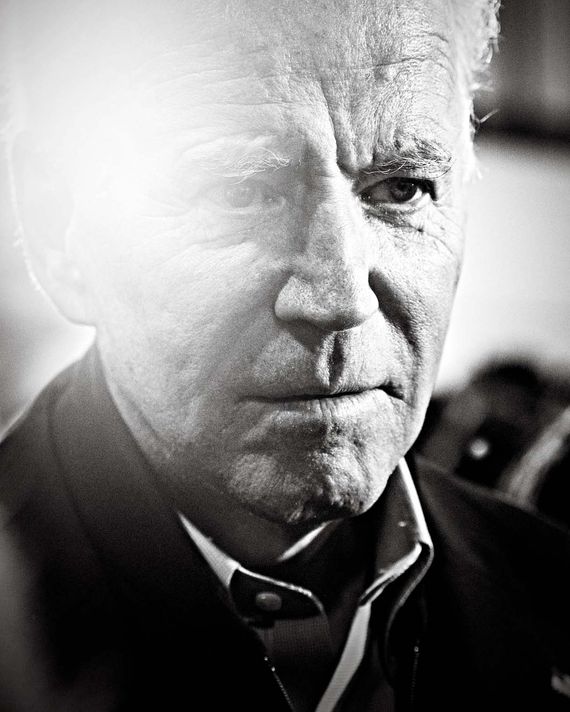

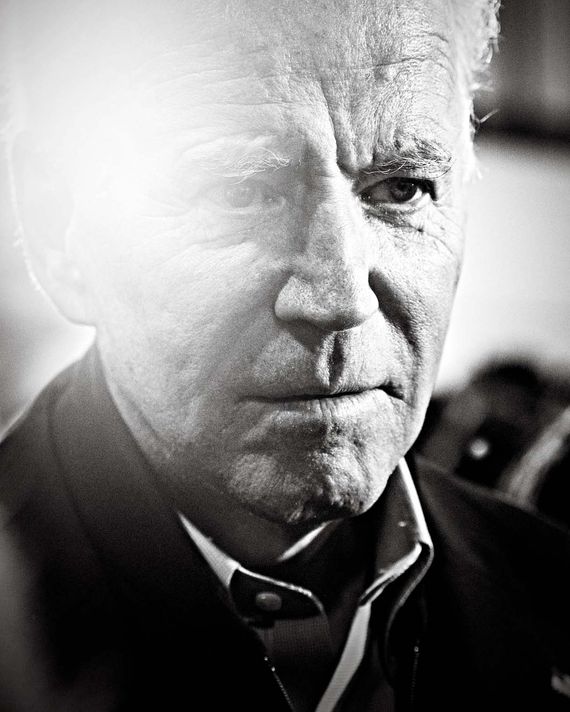

| Photo: Mark Peterson/Redux. |

Driving from work this evening I heard part of an interview with the director of a manufacturing association who discussed the harsh assessment of manufacturing CEO's who saw little demand - and therefore, hiring increases - through the end of 2020. The other possible dead weight on the economy is that many pre-pandemic jobs may not come back or, if they do, will come back very slowly. One of the things these CEO's thought would boost demand and employment was a major infrastructure initiative by the federal government, something Trump has bloviated about but which the Congressional Republicans have done nothing. Now, with America's economy upended and the political game plan for November, 2020, similarly turned upside down, presumptive Democrat nominee, Joe Biden, has radically altered what he believes his presidency must do if he defeats Der Trumpenführer, Rather than status quo ante, back to normal, restore the soul of the nation, administration, Biden - correctly, in my view - believes that a FDR style presidency and policies and programs are needed to put America back on a solid economic footing. A very long piece in

New York Magazine looks at Biden's evolution on what will need to be done. Here are highlights:

[S]ometimes looking at the small

lake abutting his backyard that bulges out from Little Mill Creek, {Joe Biden}

the self-conscious man in the Democratic middle — mocked by the activist left

throughout the primary campaign as hopelessly retrograde — considers the

present calamity and plots a presidency that, by awful necessity, he believes

must be more ambitious than FDR’s.

The former vice-president carried the

Democratic primary by relying on perceptions that he was an older, whiter, less

world-historical (and less inspiring) Barack Obama — a steady hand who seemed

more electable against a monstrous president than any of his competitors did.

The heart of his pitch, when he delivered it clearly, was status quo ante, back

to normal, restore the soul of the nation.

But in the space of just a few months,

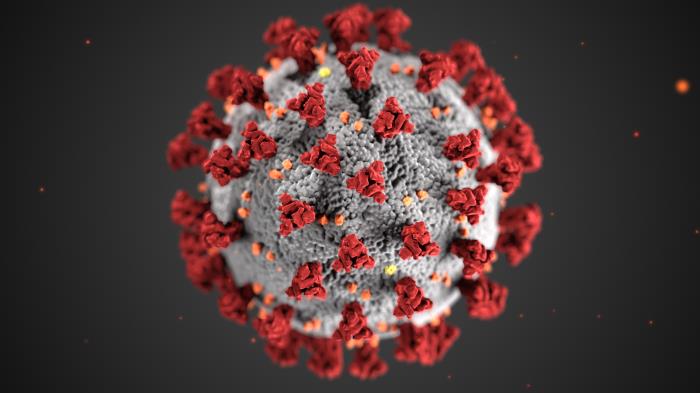

COVID-19 and the disastrous White House response appeared to have dramatically

widened Biden’s

pathway to the presidency, making the matter of moderation and electability

seem, at least for the time being, almost moot. They also changed his

perception of what the country would need from a president in January 2021 —

after not just four years of Trump but almost a full year of death and

suffering. The pandemic is breaking the country much more deeply than the Great

Recession did, Biden believes, and will require a much bigger response. No

miraculous rebound is coming in the next six months. Long

before the pandemic, he described a range of actions he’d take on day one, from

rejoining the Paris climate agreement to signing executive orders on ethics,

and he cited other matters, like passing the Equality Act for LGBTQ

protections, as top priorities. Already his recovery ambitions have grown to

include plans that would flex the muscles of big government harder than any

program in recent history. To date, the federal government has spent more than

$2 trillion on the coronavirus stimulus — nearly three times what it approved

in 2009. Biden wants more spending. “A hell of a lot bigger,” he’s said,

“whatever it takes.” He has argued that, even if you’re inclined to worry about

the deficit, massive public investment is the only thing capable of growing the

economy enough “so the deficit doesn’t eat you alive.” He has talked about

funding immense green enterprises and larger backstop proposals from cities and

states and sending more relief checks to families. He has urged immediate

increases in virus and serology testing, proposing the implementation of a

Pandemic Testing Board in the style of FDR’s War Production Board and has

called for investments in an “Apollo-like moonshot” for a vaccine and

treatment. This

is all only what he believes should be done now before he even ascends to the

presidency; by then, he thinks, the country could be in a much darker hole than

it is today, presumably requiring even more federal investment and

intervention. David Kessler, who led the Food and Drug Administration under both

George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton and has been speaking with Biden regularly

about the crisis, recently told me the former vice-president “understands that

until we have a vaccine or a therapeutic entity that can be used as a

preventative, the virus is still going to be with us and that we’re going to

constantly be putting out mini-epidemics.” [W]hile

2009 shows that spending unprecedented amounts of money alone doesn’t

necessarily make a presidency transformational, the pandemic and the economic

collapse it has produced have expanded Biden’s sense of not just how much

relief will be required but what will be possible to accomplish as part of that

recovery. Trump

accomplished one big-ticket priority: tax cuts. Obama managed two: the

stimulus, with a filibusterproof 60-vote Senate majority, and, barely,

Obama-care. While it’s impossible to tell where the country is headed, Biden’s

camp is in the disorienting position of scaling up its laundry list of

proposals to match the ambition, and the political appetite, he thinks the

American people — desperate for relief — will have in January. Biden’s

long platform has grown in recent months as the crisis has deepened. . . . Once

he began talking about a coronavirus recovery, he also started signaling more

immediate ambitions on climate, including in his multiple conversations with

Washington governor Jay Inslee. “He’s totally understood the centrality of a

clean-energy plan,” said Inslee. [O]ne

morning in late April. . . . he said into the phone, it was time they expanded

their thinking. Sure, massive gobs of federal financial help have already been

approved — unlike in 2008, he pointed out — but that still won’t be enough. Not

while the magnitude of this crisis dwarfs the last one. His advisers agreed: If

they were going to talk about lessons from history, their future calls might as

well dive into the Great Depression and World War II. Biden

is also a lifelong Democrat who likes the view from the center of the party,

enough to move rapidly to accommodate when it shifts, as it is doing now very

quickly. He may look like a milquetoast moderate to the activist left and maybe

even to you, but the party — and world — has changed so fast that even his

primary platform puts him well to the left of Obama in 2008 and, in many ways,

left of Hillary Clinton in 2016. Those close to him say he sees in the crisis

an obvious window for action. “There is no denying that the challenges a

President Biden would face in 2021 are different than anyone could have

imagined six months ago given the economic and health consequences of the

coronavirus,” Feldman, who has worked with Biden for nearly a decade, told me.

“What I’ve heard the vice-president say over and over again is this crisis is

shining a bright, bright light on so many systemic problems in our country, and

so many inequities. It is exacerbating and shining a light on

environmental-justice issues, racial inequalities, so many other problems.” Publicly,

Biden has made no secret of his displeasure with Trump’s handling of the disaster,

from his personal conduct — Biden has said the delay in distributing relief

checks in order to print Trump’s name on them “bothered me the most” — to the

administration’s failure to ensure small businesses access to relief funds

while state unemployment systems were overwhelmed. The

crisis, Biden believes, has expanded “the state of what is possible, now that

the American people have seen both the role of government and the role of

frontline workers,” said Sullivan. “He believes he has a more compelling case

to make that this is the agenda that needs to get passed.” Outwardly,

at least, Biden appears sensitive to the concerns of progressives. “He has said

this is the second time in 12 years that the American taxpayers have bailed out

American business,” Sullivan told me. The implication is that Biden has run out

of patience. “That’s fine, we should do it and protect our economy — but he

believes we have to ask our private sector to take on greater responsibility

and accountability.”

Biden

has talked openly, and seriously, about the notion of rolling out certain

Cabinet picks before he is elected as a way of giving voters a sense of what to

expect and to hit the ground running when he takes office. And he has already

begun early-stage thoughts about not just top appointments but sub-Cabinet

posts and the broader shape of his government. [H]e’s

spent plenty of his time out of the spotlight weighing his vice-presidential

options, conscious that he may effectively be picking his replacement and

therefore sending an important signal about his wishes for Democrats’ future.

His list of top contenders has long been thought to include Harris, Klobuchar,

Whitmer, and Warren, as well as Nevada senator Catherine Cortez Masto and

former Georgia gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams. As the lockdown has

dragged on, Biden has insisted his pick be ideologically “simpatico” (once

thought to be a point against Warren, though less so amid this crisis), and he

has hardened his belief that she must be prepared to take over from their first

day in office. That point — which Obama has echoed in their conversations — is

read by some in Biden’s circles as a potential knock against Abrams, who has

never held statewide elected office, and some members of Congress who’ve been

floated.

With the pandemic likely lingering through the end of the year, the prospect of four more years of Trump's mismanagement and the GOP effort to restore the Gilded Age ought to terrify most Americans - or at least those not totally blinded by racism and religious extremism.