Thoughts on Life, Love, Politics, Hypocrisy and Coming Out in Mid-Life

Saturday, March 18, 2023

Are Republicans Delusional About 2024

At this juncture, no one else in the country is as likely to be president of the United States come January 2025 as Joe Biden. Republicans telling themselves otherwise are engaged in self-delusion.

There was a palpable sense during the midterms that Republicans were playing with house money — in other words, that the political environment was so favorable that they could afford to make poor choices and still succeed. That was a mistake last year, and absent something terrible befalling Biden or the country over the next two years, is a mistake when thinking about 2024.

Biden is not a dead man walking; he’s an old man getting around stiffly. Biden is vulnerable, but certainly electable; diminished, but still capable of delivering a message; uninspiring, but unthreatening. No one is going to mistake him for a world-beater. In the RealClearPolitics polling average, he leads Donald Trump by a whopping 0.8 percent. . . . That said, he’s in the office, and no one else is. Incumbency bestows important advantages. The sitting president is highly visible, is the only civilian in the country who gets saluted by Marines walking out his door every day, has established a certain threshold ability to do the job, and can wield awesome powers to help his cause and that of his party.

Since 1992, Trump is the only incumbent to have lost, failing to join Bill Clinton, George W. Bush and Barack Obama as re-elected incumbents.

Biden was never going to be the next LBJ or FDR as a cadre of historians had seemingly convinced him early in his presidency. But he punched above his weight legislatively during his first two years, getting more out of a tied Senate and slender House majority than looked realistically possible. He’s set up to have the advantage in this year’s momentous debt-limit fight, since it’s hard to see how congressional Democrats aren’t united and congressional Republicans divided.

Biden’s age is a liability for him, but comes with a significant benefit — he does not look or sound like a radical any more than the average elderly parent or grandparent. This has enabled him to govern from the left — he would have spent even more the first two years if he could have — without appearing threatening or wild-eyed. He hasn’t restored normality to Washington so much as familiarity as the old hand who has been there since 1973 and made his first attempt at national office in 1988.

Importantly, in 2024, nothing Biden does will be considered in isolation, but instead compared to his Republican opponent. As of now, Trump has the best odds of being, once again, that adversary. Trump would have some significant chance of beating Biden, simply by virtue of being the Republican nominee, and there’s always a chance that events could be Biden’s undoing.

But Trump would probably be weaker going into a rematch than the first time around. He lost to Biden in 2020 — before he denied the results of a national election, before a fevered band of his supporters stormed the Capitol on Jan. 6, before he indulged every 2020 conspiracy theory that came across his desk, before he said the Constitution should be suspended and before he made his primary campaign partly about rebuking traditional Republicans that the GOP suburbanites he’d need in a general election probably still feel warmly about.

There’s also a strong possibility that Trump gets indicted once, or even twice, in coming months. Such charges would be perceived as unfair by Republicans — perhaps rightly so — but they would add to the haze of chaos around Trump.

Ron DeSantis or another Republican contender presumably matches up better against Biden, based on the generational contrast and the absence of Trump’s baggage alone. Yet, if a non-Trump candidate wins the nomination, he or she will have Trump in the background, probably determined to gain revenge against him or her.

Then, there’s the state of the GOP generally. It has an impressive crop of governors. Otherwise, it hasn’t seemed to take on board the lessons of the last couple of years. First, there’s a real chance that it will re-nominate Trump, after everything. Second, various state parties are irresistibly drawn to politically toxic, proven losers.

There’s no fortune quite like being lucky in your enemies, and Biden could well get a big break in this respect yet again. However much Republicans may wish he were a pushover, he’s not, and they should be acting accordingly.

Fox News Remains a Menace to Democracy

In the days following the 2020 election, Rupert Murdoch, the chair of Fox Corp and executive chairman of News Corp, was worried about one of his most lucrative businesses. Fox News had been the first major network to call Arizona for Joe Biden on Election Night, a brutal blow to Donald Trump’s reëlection hopes, and Fox viewers weren’t happy. “@FoxNews daytime ratings have completely collapsed,” Trump tweeted. “Very sad to watch this happen, but they forgot what made them successful, what got them there. They forgot the Golden Goose.”

Two days after the Arizona call, the anchor Bret Baier e-mailed Fox News’ president, Jay Wallace, to suggest retracting it. “It’s hurting us,” he wrote, proposing that the network put the state “back in his column,” referring to Trump. A few days after the election was called for Biden, Baier texted Wallace and his fellow-anchor Martha MacCallum that he was “trying to focus on the memes not the Fox hating.” MacCallum was similarly glum. “I can’t look at any of it anymore,” she wrote. “I’m watching the Queens Gambit, good escape.”

That same day, Tucker Carlson texted the Fox News producer Gavin Hadden: “Do the executives understand how much credibility and trust we’ve lost with our audience? We’re playing with fire.” Hadden was soothing. “Hopefully just a moment in time,” he wrote. “We will just ride on your shoulders.” Carlson was still jittery. “With Trump behind it,” he wrote, “an alternative like newsmax could be devastating to us.”

During the past few weeks, such texts and e-mails from Fox News hosts have been made public in Dominion Voting Systems’ defamation lawsuit against Fox, which claims that the network knowingly aired false allegations that the election was stolen from Trump, at least in part, with the help of Dominion’s products. “I hate him passionately,” Carlson said of Trump in one text message. According to Laura Ingraham, another of the network’s prime-time hosts, Trump’s attorney Sidney Powell, who peddled election lies on the network, was “a bit nuts.”

Much of the non-Fox News media, meanwhile, has crowed at tangible evidence of the network’s duplicitous coverage and speculated about whether any of it will force Fox News to reform. “The documents lay bare that the channel’s business model is not based on informing its audience, but rather on feeding them content—even dangerous conspiracy theories—that keeps viewers happy and watching,” CNN’s Oliver Darcy wrote. Margaret Sullivan, in a column for the Guardian, asked if a Fox News loss in the lawsuit might “make coverage more responsible.”

But, despite the bad headlines, Fox News has little incentive to change its ways. For one thing, the network’s loyal audience is likely to remain glued to their screens, especially as a contested G.O.P. Presidential primary plays out on-air over the next two years. . . . “The audience is not going anywhere,” they said. “Fox may be forced to read an apology on air or something, but the audience still loves the product. It’s basically the W.W.E. for this kind of world.” . . . What’s more, Fox News’ parent company has pursued a successful, if conservative, fiscal strategy in the past few years.

Of course, a loss in the Dominion trial would have an impact. Dominion is seeking $1.6 billion in damages, and Fox is facing a similar lawsuit from Smartmatic, another voting-tech company, which is claiming $2.7 billion in damages. Assuming the Dominion case goes to trial next month instead of settling out of court—something that close watchers of the proceedings think is more and more likely—Fox risks a hefty financial burden. Although Dominion might get only a fraction of the $1.6 billion in compensatory damages if it wins at trial—essentially, revenue the company can prove that it lost because of the defamation—Sandy Bohrer, a former partner at a large law firm who defended defamation suits for decades, said that the network could face huge exposure on punitive damages. “It’s a very, very unsympathetic defendant,” he said. “I have never seen this bad a case for a defendant. Ever.” A number of law firms are already soliciting to file suits on behalf of Fox Corp shareholders. Even still, Fox could likely absorb a sum in the billions without bankrupting its business.

But Fox News could still find itself imperilled if its pro-Trump audience turns against some of its biggest stars, such as Carlson. In one of the released messages, Carlson called Trump “a demonic force, a destroyer.” . . . So far, though, Trump and Carlson are playing nice. . . . “He doesn’t hate me, or at least, not anymore!” Trump wrote on Truth Social, of Carlson.

But if the disclosures in the Dominion case have revealed anything it’s that, for Fox News, there’s no money in tacking to the center. Consistently, the network has shied away from covering political realities that would upset its audience. In the wake of the riot on the Capitol, Ingraham suggested on her show that the violence was in part to blame on Antifa agitators, and Carlson, in his own producer’s words, spent his show on January 6th “beating around the bush” about what was actually happening. For all the behind-the-scenes hand-wringing at Fox News about the dangerous untruths being spread by Trump in the wake of the 2020 election, the programming tone never really shifted. . . . Even though Murdoch has admitted that he didn’t believe the election was fraudulent, he allowed his network to continue pushing falsehoods.

At this point, the only thing that might trigger an internal reckoning about the role of Fox News in American civil life is the departure of its owner. Murdoch, who is ninety-two, is a committed conservative, as is his eldest son and preferred successor, Lachlan. In his deposition, Lachlan spoke of his faith in the power of the network to withstand the post-election turbulence.

But there is a speculative scenario in which, at some point in the future, Murdoch’s youngest son, James, makes a play for the top spot and outmaneuvers Lachlan by securing the support of two of his sisters, Prudence and Elisabeth. (Yes, this is the stuff that premier-cable dreams are made of.) James and his wife donated to various democracy organizations and Democratic causes during the Trump years, and his sisters are thought to be more politically aligned with him. Elisabeth was a Barack Obama supporter; Prudence, who’s largely stayed out of the limelight, is a little more difficult to peg. Perhaps, with the help of his sisters, James could restructure Fox, dialling back its most extreme rhetoric to create a network that is center-right, with politics more in line with something like the editorial board of the Wall Street Journal. Of course, he would have to persuade the company’s board to go along with the plan, which seems like a stretch, given the success of Fox Corp in its current iteration. One former Fox executive seemed skeptical that such a shift would happen. “Trump has so crazed both the left and the right,” they said. “Extremists screaming at each other gets quicker ratings.”

Friday, March 17, 2023

Florida's Dangerous Push to Rewrite History

The nitty-gritty process of reviewing and approving school textbooks has typically been an administrative affair, drawing the attention of education experts, publishing executives and state bureaucrats.

But in Florida, textbooks have become hot politics, part of Gov. Ron DeSantis’s campaign against what he describes as “woke indoctrination” in public schools, particularly when it comes to race and gender. Last year, his administration made a splash when it rejected dozens of math textbooks, citing “prohibited topics.”

Now, the state is reviewing curriculum in what is perhaps the most contentious subject in education: social studies.

In the last few months, as part of the review process, a small army of state experts, teachers, parents and political activists have combed thousands of pages of text — not only evaluating academic content, but also flagging anything that could hint, for instance, at critical race theory.

A prominent conservative education group, whose members volunteered to review textbooks, objected to a slew of them, accusing publishers of “promoting their bias.” At least two publishers declined to participate altogether.

And in a sign of how fraught the political landscape has become, one publisher created multiple versions of its social studies material, softening or eliminating references to race — even in the story of Rosa Parks — as it sought to gain approval in Florida.

It is unclear which social studies textbooks will be approved in Florida, or how the chosen materials might address issues of race in history. The state is expected to announce its textbook decisions in the coming weeks.

The Florida Department of Education, which mandates the teaching of Black history, emphasized that the requirements were recently expanded, including to ensure students understood “the ramifications of prejudice, racism and stereotyping on individual freedoms.”

But Mr. DeSantis, a top Republican 2024 presidential prospect, also signed a law last year known as the Stop W.O.K.E. Act, which prohibits instruction that would compel students to feel responsibility, guilt or anguish for what other members of their race did in the past, among other limits.

Florida — along with California and Texas — is a major market for school textbook publishing, a $4.8 billion industry.

It is among more than a dozen states that approve textbooks, rather than leaving decisions only to local school districts. Every few years, Florida reviews textbooks for a particular subject and puts out a list that districts can choose from.

The Florida Citizens Alliance, a conservative group, has urged the state to reject 28 of the 38 textbooks that its volunteers reviewed, including more than a dozen by McGraw Hill, a major national publisher.

The alliance, whose co-founders served on Mr. DeSantis’s education advisory team during his transition to governor, has helped lead a sweeping effort to remove school library books deemed as inappropriate, including many with L.G.B.T.Q. characters. It trained dozens of volunteers to review social studies textbooks.

In a summary of its findings submitted to the state last month, the group complained that a McGraw Hill fifth-grade textbook, for example, mentioned slavery 189 times within a few chapters alone. Another objection: An eighth-grade book gave outsize attention to the “negative side” of the treatment of Native Americans, while failing to give a fuller account of their own acts of violence, such as the Jamestown Massacre of 1622, in which Powhatan warriors killed more than 300 English colonists.

Of the nearly 20 publishers who applied in Florida, one major player was not on the list: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, or HMH.

HMH, which won approval for social studies textbooks during Florida’s last review six years ago, was among the publishers whose math textbooks were initially rejected last year for “prohibited topics” and other unsolicited strategies, such as critical race theory or social emotional learning. (The textbooks were later approved after what HMH described as minor revisions.)

In an attempt to cater to Florida, at least one publisher made significant changes to its materials, walking back or omitting references to race, even in its telling of the Rosa Parks story.

The New York Times compared three versions of the company’s Rosa Parks story, meant for first graders: a current lesson used now in Florida, an initial version created for the state textbook review and a second updated version.

Some of the material was provided by the Florida Freedom to Read Project, a progressive parent group that has fought book ban efforts in the state, and confirmed by The Times.

In the current lesson on Rosa Parks, segregation is clearly explained: “The law said African Americans had to give up their seats on the bus if a white person wanted to sit down.”

But in the initial version created for the textbook review, race is mentioned indirectly. In the updated version, race is not mentioned at all. “She was told to move to a different seat,” the lesson said, without an explanation of segregation.

Studies Weekly made similar changes to a fourth-grade lesson about segregation laws that arose after the Civil War. In the initial version for the textbook review, the text routinely refers to African Americans, explaining how they were affected by the laws. The second version eliminates nearly all direct mentions of race, saying that it was illegal for “men of certain groups” to be unemployed and that “certain groups of people” were prevented from serving on a jury.

Studies Weekly said it was trying to follow Florida’s standards, including the Stop W.O.K.E. Act. “All publishers are expected to design a curriculum that aligns with” those requirements, John McCurdy, the company’s chief executive, said in an email.

Thursday, March 16, 2023

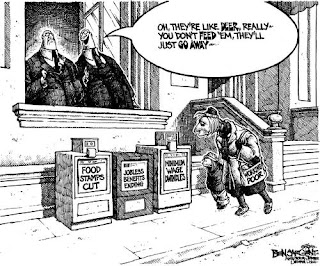

America's Poverty: American Style Deprivation

The United States has a poverty problem.

A third of the country’s people live in households making less than $55,000. Many are not officially counted among the poor, but there is plenty of economic hardship above the poverty line. And plenty far below it as well. According to the Supplemental Poverty Measure, which accounts for government aid and living expenses, more than one in 25 people in America 65 or older lived in deep poverty in 2021, meaning that they’d have to at minimum double their incomes just to reach the poverty line.

Programs like housing assistance and food stamps are effective and essential, protecting millions of families from hunger and homelessness each year. But the United States devotes far fewer resources to these programs, as a share of its gross domestic product, than other rich democracies, which places America in a disgraced class of its own on the world stage.

On the eve of the pandemic, in 2019, our child poverty rate was roughly double that of several peer nations, including Canada, South Korea and Germany. Anyone who has visited these countries can plainly see the difference, can experience what it might be like to live in a country without widespread public decay. When abroad, I have on several occasions heard Europeans use the phrase “American-style deprivation.”

Poverty is measured at different income levels, but it is experienced as an exhausting piling on of problems. Poverty is chronic pain, on top of tooth rot, on top of debt collector harassment, on top of the nauseating fear of eviction. It is the suffocation of your talents and your dreams. It is death come early and often. Between 2001 and 2014, the richest women in America gained almost three years of life, while the poorest gained just 15 days. Far from a line, poverty is a tight knot of humiliations and agonies, and its persistence in American life should shame us.

All the more so because we clearly have the resources and know-how to effectively end it. The bold relief issued by the federal government during the pandemic — especially expanded child tax credits, unemployment insurance and emergency rental assistance — plunged child poverty . . . . “In six months — six months — we reduced child poverty almost by half. We know how to do this.”

We do — but predictably, some Americans with well-fed and well-housed families complained that the country could no longer afford investing so deeply in its children. At best, this was a breathtaking failure of moral imagination; at worst, it was a selfish, harmful lie.

We could fund powerful antipoverty programs through sensible tax reform and enforcement. A recent study estimates that collecting all unpaid federal income taxes from the top 1 percent — not raising their taxes, mind you, just putting an end to their tax evasion — would add $175 billion a year to the public purse. That’s enough to more than double federal investment in affordable housing or to re-establish the expanded child tax credit.

The hard part isn’t designing effective antipoverty policies or figuring out how to pay for them. The hard part is ending our addiction to poverty.

Poverty persists in America because many of us benefit from it. We enjoy cheap goods and services and plump returns on our investments, even as they often require a kind of human sacrifice in the form of worker maltreatment. We defend lavish tax breaks that accrue to wealthy Americans, starving antipoverty initiatives. And we build and defend exclusive communities, shutting out the poor and forcing them to live in neighborhoods of concentrated disadvantage.

Most Americans — liberals and conservatives alike — now believe people are poor because “they have faced more obstacles in life,” not because of a moral failing. Long overdue, however, is a reckoning with the fact that many of us help to create and uphold those obstacles through the collective moral failing of enriching ourselves by impoverishing others. Poverty isn’t just a failure of public policy. It’s a failure of public virtue.

Ending poverty in America will require both short- and long-term solutions: strategies that stem the bleeding now, alongside more enduring interventions that target the disease and don’t just treat the symptoms.

For example, to address the housing crisis forcing most poor renting families to dedicate at least half of their income to rent and utilities, we need to immediately expand housing vouchers that reduce the rent burden. But we also need to push for more transformative solutions like scaling up our public housing infrastructure, enlarging community land banks, and providing on-ramps to homeownership for low-income families.

When it comes to work, we should attack labor exploitation head-on by finding ways to even the playing field between workers and bosses — supporting collective bargaining, for instance . . . . At the bare minimum, Congress should increase the federal minimum wage — which hasn’t been raised since July 2009 — and, like dozens of other countries, allow the federal government to routinely adjust the wage without legislative approval, ensuring that workers wouldn’t have to wait around another 13-plus years (and counting!) for a pay bump.

Poverty abolitionism isn’t just a political project, after all; it’s a personal one, too. For starters, just as many of us are now shopping and investing in ways that address climate change, we can also do so with an eye toward economic justice. If we can, we should reward companies that treat their employees well and shun those with a track record of union-busting and exploitation. To do so, we can consult organizations like B Lab, which certifies companies that meet high social and environmental standards, and Union Plus, which curates lists of union-made products.

These everyday decisions can add up to something. If more of us adopted poverty abolitionism as a way of living — and of seeing the world and imaging a better one — that behavior would spread, which in turn could redefine what is socially acceptable and what is believed possible.

We can also disrupt all the quotidian ways we normalize the status quo. It is commonplace for privileged Americans to gripe about taxes. But doing so ignores how the country’s welfare state does much more to subsidize affluence — with tax breaks for college savings accounts, wealth transfers, and more — than to alleviate poverty.

What if, the next time a co-worker brought up the topic, we talked about that instead? What if we gawked at the fact that homeowners pocket billions of dollars each year because of the mortgage interest deduction, an absurd cutout that flows primarily to well-off Americans, while most poor renting families receive no government housing assistance?

This rich country has the means to abolish poverty. Now we must find the will to do so — the will, not to reduce poverty, but to end it.

Wednesday, March 15, 2023

The Moscow Primary - Will DeSantis Flame Out?

Governor DeSantis gave strong hints that he intends to compete with Donald Trump for Moscow’s love last month. He made it explicit last night. One could argue that DeSantis scored a political trifecta for the pro-Putin crowd: he refused to call Ukrainian victory an objective; nor would he call it a vital American interest; and he did all this response to Tucker Carlson’s questionnaire, no less. . . . For the uninitiated, Tucker Carlson is inarguably the most watched Putin sympathizer in America.

DeSantis has made it abundantly clear: he is entering the Moscow Primary. Now he and Trump will have to out-appease each other to win over the Kremlin. I’d still give the edge to Trump (he’s had a lot more practice), but DeSantis isn’t going down without a fight. Moreover, unlike the primary and caucuses over here, there is only one voter in the Moscow Primary. He’s keeping his preference secret … for now.

Ouch! Harsh, but true. As for where DeSantis goes should he win the GOP primary, the piece in The Atlantic argues that by winning the Moscow primary, DeSantis is making the general election difficult to win. Here are highlights:

Florida Governor Ron DeSantis has long sought to avoid taking a position on Russia’s war in Ukraine. On the eve of the Russian invasion, 165 Florida National Guard members were stationed on a training mission in Ukraine. They were evacuated in February 2022 to continue their mission in neighboring countries. When they returned to Florida in August, DeSantis did not greet them. He has not praised, or even acknowledged, their work in any public statement.

DeSantis did find time, however, to admonish Ukrainian officials in October for not showing enough gratitude to new Twitter owner Elon Musk. (Musk returned the favor by endorsing DeSantis for president.) On tour this month to promote his new book, DeSantis has clumsily evaded questions about the Russian invasion. When a reporter for The Times of London pressed the governor, DeSantis scolded him: “Perhaps you should cover some other ground? I think I’ve said enough.”

So last night, DeSantis delivered a more definitive answer on Tucker Carlson’s Fox News show.

DeSantis’s statement on Ukraine was everything that Russian President Vladimir Putin and his admirers could have wished for from a presumptive candidate for president. The governor began by listing America’s “vital interests” in a way that explicitly excluded NATO and the defense of Europe. He accepted the present Russian line that Putin’s occupation of Ukraine is a mere “territorial dispute.” He endorsed “peace” as the objective without regard to the terms of that peace, another pro-Russian talking point. He conceded the Russian argument that American aid to Ukraine amounts to direct involvement in the conflict. He endorsed and propagated the fantasy—routinely advanced by pro-Putin guests on Fox talk shows—that the Biden administration is somehow plotting “regime change” in Moscow. . . . . He ended by flirting with the idea of U.S. military operations against Mexico, an idea that originated on the extreme right but has migrated toward the Republican mainstream.

A careful reader of DeSantis’s statement will find that it was composed to provide him with some lawyerly escape hatches from his anti-Ukraine positions. For example, it ruled out F-16s specifically rather than warplanes in general. But those loopholes matter less than the statement’s context. After months of running and hiding, DeSantis at last produced a detailed position on Ukraine—at the summons of a Fox talking head.

DeSantis is a machine engineered to win the Republican presidential nomination. The hardware is a lightly updated version of donor-pleasing mechanics from the Paul Ryan era. The software is newer. DeSantis operates on the latest culture-war code: against vaccinations, against the diversity industry, against gay-themed books in school libraries. The packaging is even more up-to-the-minute. Older models—Mitt Romney, Jeb Bush—made some effort to appeal to moderates and independents. None of that from DeSantis. He refuses to even speak to media platforms not owned by Rupert Murdoch.

The problem that Republicans confront with this newly engineered machine is this: Have they built themselves a one-stage rocket—one that achieves liftoff but never reaches escape velocity? The DeSantis trajectory to the next Republican National Convention is fast and smooth.

DeSantis has been going up in the polls, too. According to Quinnipiac, Donald Trump’s lead over DeSantis in a four-way race between them, Mike Pence, and Nikki Haley has shriveled to just two points.

After that midpoint, however, the DeSantis flight path begins to look underpowered.

Florida Republicans will soon pass—and DeSantis pledged he would sign—a law banning abortion after six weeks. That bill is opposed by 57 percent of those surveyed even inside Florida. Another poll found that 75 percent of Floridians oppose the ban. It also showed that 77 percent oppose permitless concealed carry, which DeSantis supports, and that 61 percent disapprove of his call to ban the teaching of critical race theory as well as diversity, equity, and inclusion policies on college campuses. As the political strategist Simon Rosenberg noted: “Imagine how these play outside FL.”

But even this understates the DeSantis design flaw.

More dangerous than the unpopular positions DeSantis holds are the popular positions he does not hold. What is DeSantis’s view on health care? He doesn’t seem to have one. President Joe Biden has delivered cheap insulin to U.S. users. Good idea or not? Silence from DeSantis. There’s no DeSantis jobs policy; he hardly speaks about inflation. Homelessness? The environment? Nothing. Even on crime, DeSantis must avoid specifics, because specifics might remind his audience that Florida’s homicide numbers are worse than New York’s or California’s.

DeSantis just doesn’t seem to care much about what most voters care about. And voters in turn do not care much about what DeSantis cares most about. . . . . “It’s mostly college-educated white women that are going to decide this thing. Republicans win on pocketbook issues with them, not busing migrants across the country.”

A new CNN poll finds that 59 percent of Republicans care most that their candidate agrees with them on the issues; only 41 percent care most about beating Biden. . . . .DeSantis will be a candidate of the Republican base, for the Republican base. Like Trump, he delights in displaying his lack of regard for everyone else. Trump, however, is driven by his psychopathologies and cannot emotionally cope with disagreement. DeSantis is a rational actor and is following what somebody has convinced him is a sound strategy. It looks like this:

- Woo the Fox audience and win the Republican nomination.

- ??

- Become president.

Written out like that, you can see the missing piece. DeSantis is surely intelligent and disciplined enough to see it too. But the programming installed in him prevents him from acting on what he sees. His approach to winning the nomination will put the general election beyond his grasp. He must hope that some external catastrophe will defeat his Democratic opponent for him—a recession, maybe—because DeSantis is choosing a path that cannot get him to his goal.

Tuesday, March 14, 2023

The Boys on the Right Who Cried "Woke!"

As soon as it was clear that Silicon Valley Bank would not survive the weekend, conservative influencers and Republican politicians had a culprit in sights.

Wokeness. “They were one of the most woke banks,” Representative James Comer, the top Republican on the House Oversight Committee, said during a segment on Fox News.

The governor of Florida, Ron DeSantis, also spoke to Fox about the collapse of the bank, and he also blamed the bank’s diversity programs.

A Saturday headline in The New York Post declared, “While Silicon Valley Bank Collapsed, Top Executive Pushed ‘Woke’ Programs.” And over at The Wall Street Journal, Andy Kessler wondered if “the company may have been distracted by diversity demands.”

On Twitter, a number of prominent conservatives took this message and ran with it. Donald Trump Jr. said that “SVB is what happens when you push a leftist/woke ideology and have that take precedent over common sense business practices.” Stephen Miller, a key White House aide to President Donald Trump, accused the bank of wasting its funding on “trendy woke BS.” And Senator Josh Hawley, Republican of Missouri, complained that “these SVB guys spend all their time funding woke garbage (‘climate change solutions’) rather than actual banking and now want a handout from taxpayers to save them.”

It is unclear whether these conservatives are working from the same memo or just share the same narrow obsession. Regardless, there is no evidence that D.E.I. or any other diversity initiative is responsible for the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank. It is nonsense. . . . this deflection is worth noting for what it represents: the relentless effort to mystify real questions of political economy in favor of endless culture war conflict.

The real story behind the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank has much more to do with the political and economic environment of the previous decade than it does with “wokeness,” a word that signifies nothing other than conservative disdain for anything that seems liberal.

As its name suggests, Silicon Valley Bank was tied tightly into the financial infrastructure of the tech industry. Founded in 1983, it claimed to bank for “nearly half of all US venture-backed start-ups” and it worked closely with many venture capital firms. It is risky for a bank to take most of its deposits from a single, tightly-knit industry. But for much of the last decade, low interest rates, easy money and cheap loans meant that this industry was on the upswing. As tech boomed, so did S.V.B.

“Flush with cash from high-flying start-ups,” my newsroom colleague Vivian Giang explains, Silicon Valley Bank “did what most of its rivals do: It kept a small chunk of its deposits in cash and it used the rest to buy long-term debt like Treasury bonds.” As long as interest rates stayed low, those bonds promised safe returns.

Interest rates did not stay low. To fight inflation and reduce the price of consumer goods, the Federal Reserve raised interest rates seven times in 2022. With each increase, Silicon Valley Bank lost money on its bonds. Worse, the interest rate surge affected venture capital firms and the entire world of tech start-ups, harming the bank’s portfolio as those companies shed value and reduced deposits.

Worried clients began to withdraw more money, which spooked investors, a development that pushed more clients to withdraw even more money. (Peter Thiel’s Founders Fund reportedly called for its start-ups to pull their cash while they still could.) On Friday, as the bank run gained steam, California’s financial regulatory agency announced that it had taken possession of the bank and placed it under the receivership of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.

That is the immediate situation. But there is a larger context. Silicon Valley Bank had a significant number of large and uninsured depositors — clients with accounts totaling more than the up to $250,000 guaranteed by the F.D.I.C.

Ten years ago, the bank might have been subject to a stress test by the Federal Reserve, which would have forced the bank to diversify its investments.

But in 2018, Trump signed a bipartisan bill that shielded regional banks like Silicon Valley from regulatory scrutiny under the Dodd-Frank Act. Greg Becker, the bank’s chief executive, actually lobbied for this change, urging the government to raise the threshold it used for judging systematic risk, from $50 billion in assets to $250 billion in assets.

It’s not as if no one thought this collapse could happen. “The failure of Silicon Valley Bank is a direct result of an absurd 2018 bank deregulation bill signed by Donald Trump that I strongly opposed,” Senator Bernie Sanders said in a statement on Sunday. Senator Elizabeth Warren made a similar point in an essay published in The Times on Monday, in which she also mentioned the failure of New York-based Signature Bank in the immediate aftermath of S.V.B.’s collapse . . . . .

All of this is to say that if you want to understand the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, you have to understand the political environment that led Congress to loosen regulations on regional banking institutions. You have to understand the interests involved, the ideologies involved and the personalities involved, like DeSantis, who voted for the deregulation bill as a congressman.

The people who blame “wokeness” for the collapse of a bank do not want you to understand or even think about the political economy of banking in the United States. They want to deflect your attention away from the real questions and turn it toward a manufactured cultural conflict. And the reason they want to do this is to obscure the extent to which they and their allies are complicit in — or responsible for — creating an environment in which banks collapse for lack of appropriate regulation.

This, again, is just one example of how bad actors and interested parties try to obscure serious questions about the structure of our society with claims that serve only to muddy the waters. You don’t have to look hard to find others.

Put simply, you show me a scene from the so-called culture wars, and I’ll show you what’s behind it: a real issue with real stakes for real people.

Monday, March 13, 2023

Can the GOP Escape Its Frankenstein Monster?

When former New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie took his turn on stage at a Republican donor conference here late last month, he brought the crowd alive with a rousing and extended denunciation of Donald Trump.

Demanding his party “stop whispering” about their unease with Trump, Christie excoriated Trump for falsely claiming the 2020 election was stolen, propelling a series of lackluster candidates last year and generally presiding over the decline of the GOP over the last half decade.

“If we continue down this road it’s a road that will lead us to another four years of Joe Biden,” Christie warned, repurposing Trump’s memorable vow that Republicans would become tired of winning on his watch to lament their “losing and losing and losing and losing.”

Yet what was even more revealing about Christie’s half-hour remarks, a recording of which I obtained, was the less direct but unmistakable and certainly not whispered criticism he leveled at Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis. Christie called DeSantis’s warnings about sliding into a proxy war with China “one of the most naïve things I’ve ever heard in my life” — arguing America is already locked in such a conflict; he told the donors “don’t be fooled by false choices” being pushed by “a fellow governor,” a reference to DeSantis’s argument that Biden was too focused on Ukraine’s border at the expense of America’s border; and, most pointedly, Christie wondered how exactly “they teach foreign policy in Tallahassee.”

Immediately after saying “he is the problem” of the former president, Christie concluded his pitch by warning that the safer course was not to “just nominate Trump Lite.”

The Stop Trump campaign among Republican elites is off to a quick start. Most every weekend since the start of this year there’s been some sort of gathering of donors, strategists and lawmakers in a warm weather state. And while the hotel ballrooms, lobby bars and presidential libraries may change, the overarching goal is consistent: how not to be saddled with perhaps the one candidate who may lose to Biden.

As DeSantis heads to Iowa Friday for what’s effectively the start of his presidential bid, his initial strength with Republican contributors and voters alike is prompting the other would-be candidates to divide or at least pair their attacks. With Trump appearing to have an unshakable core of support, and the nature of the primary shaping up to be who can emerge as the strongest alternative to him, the rest of the potential field plainly feels pressure to dislodge DeSantis from his early perch as that candidate.

Clearly alarmed about being portrayed by Trump as overly tied to the so-called establishment, DeSantis has cultivated right-wing leaders and influencers, inviting them to his inauguration in January and his own donor retreat last month in Florida. As significant, he’s deepened his friendship with some of the best-known hard-liners in Congress and is poised to soon deploy them as surrogates.

While DeSantis is building the message and team of messengers to guard his right MAGA flank from Trump, though, much of the rest of the field is taking aim with hopes of raising doubts about him among non-MAGA voters.

DeSantis said last month in a Fox News interview that it wasn’t wise to tempt a wider war, downplayed the prospect Russia may invade other European countries and denounced what he called Biden’s “blank-check” aid to Ukraine. What he didn’t do was take a forceful stance aligning himself with the populist or internationalist wing of his party on the larger question of America’s role in the conflict.

Speaking on the first anniversary of the Ukraine war, Pence rejected, with a characteristic reference to scripture, DeSantis’s uncertain trumpet. “We’ve got to speak plainly to the American people about the threats that we face,” said the former vice president, calling for “strong American leadership on the world stage.”

Firmly aligning himself with the pre-Trump party from which he came, Pence said he had “no illusions about Putin,” invoked Ronald Reagan and said when “Russia is on the move, when authoritarian regimes like China are threatening their neighbors, we need to meet that moment with American strength.”

“If we surrender to the siren song of those in this country who argue that America has no interest in freedom’s cause, history teaches we may soon send our own into harm’s way to defend our freedom and the freedom of nations in our alliance,” Pence said, standing in front of side-by-side American and Ukrainian flags and declaring there’s only “room for champions of freedom” in the GOP.

Which may come as a surprise to the Republican frontrunner and much of Fox News’s primetime lineup.

But those would-be candidates hoping to compete for the 60-plus percent of primary voters unlikely to back Trump, a demographic which overlaps with the more hawkish wing of the party, see their opening.

“I’m absolutely shocked when I hear Republicans talk about not defending Ukraine and not ensuring America is strong across the planet,” New Hampshire Gov. Chris Sununu told me after his address to the donors in Austin, which was officially sponsored by the Texas Voter Engagement Project but largely convened by Karl Rove

The growing concern about DeSantis from the rest of the modest-sized field is understandable when you consider his early strengths, the long history of Republican presidential primaries and the unique nature of this race.

No other Republican is remotely as close to Trump in the polls as the Florida governor, nor do any other candidates have the nearly $100 million he’s sitting on from his state races. And they’re not drawing the sort of crowds to party dinners, or protesters, DeSantis is commanding.

What makes this contest similar to the others is that it begins with an obvious frontrunner, a hallmark of GOP nomination battles that often rewarded vice presidents, previous candidates or those who were seen as having waited for their turn. Usually, it was those early leaders who were targeted by the rest of the candidates, often from the right.

Yet what’s different about 2024, and what’s driving the growing urgency to stymie DeSantis, is that Trump’s loyalists are so committed and his skeptics so determined to find an alternative that the market of competition is shifting to the race-within-a-race: the battle to be the last Republican standing against the former president.

“We learned this back in 2016,” Mick Mulvaney, the former Freedom Caucus lawmaker turned Trump chief of staff told me, his exasperation radiating through the phone.

Mulvaney, who said he doesn’t think Trump can win a general election, attended DeSantis’s donor retreat and recalled how the governor regaled the crowd with how he performed better with women and Hispanic voters last year than in his first gubernatorial bid — “and not with identity politics.”

While he said he’s not likely to endorse DeSantis, Mulvaney urged the other Republicans to keep their fire on the former president. “In order to beat Trump you have to beat Trump,” he said.

It’s easy to see why somebody like Mulvaney is so emphatic when you consider some of the early polling, including a private survey I obtained from Differentiators Data, a GOP consulting firm.

When they tested a variety of potential candidates among Virginia Republican primary voters, DeSantis was only leading Trump by three points. Yet when the firm narrowed the choice to only the two top candidates it wasn’t even close: DeSantis was leading Trump by 17.

Sunday, March 12, 2023

Countering the Growing Threat of Christian Nationalist Violence

Troubling new details regarding the violent propensity of Christian nationalism have been revealed by a new survey on American Christian nationalism released last month. According to the PRRI/Brookings Institution data, adherents of Christian nationalism are almost seven times as likely as those who reject it to support political violence. A stunning 40 percent of Christian nationalism supporters believe that “true American patriots may have to resort to violence in order to save our country.”

The revelations of the survey do not bode well for the future of Christian nationalist violence in America. Over the past decade, I’ve analyzed hundreds of religious militant groups around the world. My studies have consistently found that the tipping point toward violence occurs primarily when religious identity and national identity become intertwined. As these identities fuse, historically and culturally dominant faith communities come to see themselves as the victims of encroachment by minority faith traditions. This perceived victimization results in a “persecution complex,” with little regard for the degree of historical or cultural dominance the community enjoys. What matters is that majoritarian religious communities feel like they’re victims.

Perceived victimization often stems from changing religious landscapes, like the unprecedented rise of “the nones” in the US. This new pluralism is seen as threatening to the privileged station of the majority religious tradition, often prompting the self-segregation of majority communities from the rest of society. The resulting echo chamber further reinforces the paranoia surrounding the victim narrative.

Increasingly, members of religious majorities see violence as an acceptable way to beat back the threat posed by religious heterogeneity. . . . We see evidence supportive of this thesis in countries as diverse as Brazil, Central African Republic, Pakistan, India, and Myanmar, where vigilantes from dominant religious communities routinely attack the homes, businesses, and houses of worship of religious minorities with impunity.

As I show in my recent book The Global Politics of Jesus: A Christian Case for Church-State Separation, similar dynamics appear to be unfolding in the United States today, where a combination of forces—new cultural mores surrounding gender and sexuality, increasing religious diversity, and declining numbers of Christians—are disrupting the religious landscape and leading to a sense of angst among American Christians that their country is turning its back on what they believe to be its Christian heritage.

Consider the words of Kandiss Taylor, a former candidate for governor of Georgia: “The good thing about the First Amendment is that if you’re a Jew or you’re a Muslim or you’re a Buddhist, you still get to worship your god because you’re in America. But you don’t get to silence us,” she declared last year to an approving audience. . . . . Taylor failed to mention that the United States is a Christian-majority country where Jews, Muslims, and Buddhists collectively comprise only about four percent of the total population. Similar sentiments have been expressed by a number of other prominent politicians with Christian nationalist inclinations, including Florida governor Ron Desantis, Georgia congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene, Colorado congresswoman Lauren Boebert, and Texas senator Ted Cruz.

This fusion of religion and nation has created a fertile breeding ground for a culture of violence to take root. Of course, Christian nationalist violence in the United States is nothing new. . . But Christian nationalist violence has also experienced a resurgence in recent years. Christian nationalist ideology figured prominently in the violence of the 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia; mass shootings at an African American church in Charleston, South Carolina in 2015, a Pittsburgh synagogue in 2018, at three different spas in the Atlanta-area in 2021, and at a grocery store in Buffalo, New York in 2022; as well as dozens of other instances of vigilante violence against religious minorities. And, of course, it was on full display during the 2021 Capitol insurrection two years ago.

Given the dynamics present in the United States today (just look at last week’s CPAC), we can expect Christian nationalist violence to increase in the future. Paradoxically, the thumping Christian nationalist political candidates took during the 2022 midterm elections—including the failed gubernatorial candidacies of Pennsylvania’s Doug Mastriano, Maryland’s Dan Cox, and Arizona’s Kari Lake—will likely deepen the sense of embattlement among Christian nationalists, prompting a backlash.

Fortunately, not all is lost. My research also shows that religious violence dissipates when these narratives are discredited from within the religious traditions from which they arise. . . . . Christian communities where Christian nationalism is most likely to thrive—must offer a counternarrative that can demonstrate that there are other, equally valid expressions of Christianity that respect this nation’s diversity and secular foundation. The amplification of these voices is paramount to countering the scourge of Christian nationalism and the violence it has helped produce.