Thoughts on Life, Love, Politics, Hypocrisy and Coming Out in Mid-Life

Saturday, July 09, 2022

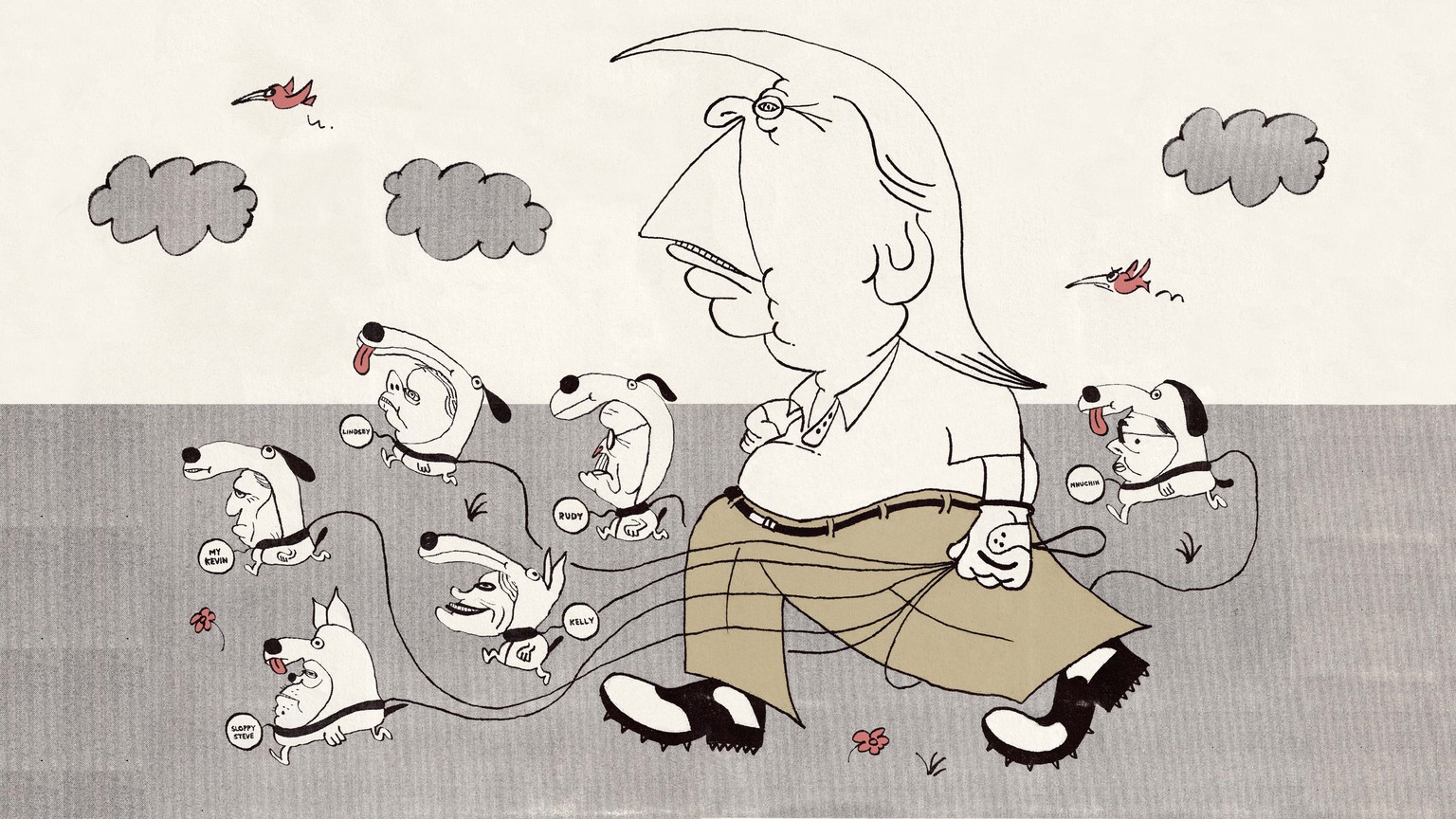

The Most Pathetic Men in America

|

| Image by Gabriel Carr |

When he wasn’t melting down over how “very badly” he was treated or acting like a seditious lunatic, Donald Trump could be downright serene in certain Washington settings—and never more so than when he would swan in for dinner at the Trump International Hotel, a few blocks down Pennsylvania Avenue from the White House and the only other place where he would ever agree to eat.

Unlike the Obamas, who would sneak out for date nights at trendy restaurants, Trump was hardly discreet when he went out to dinner. For Trump, a big, applauded entrance was as essential to the experience as the shrimp cocktail, fries, and 40-ounce steak. Each night, assorted MAGA tourists and administration bootlickers would descend on the atrium bar on the small chance they’d get to glimpse Trump himself in his abundant flesh . . . .

Lots of Washington reporters would hang around the establishment, too. We could always pick up dirt that Trump and his groveling legions tracked in. The place was crawling with them, these hollowed-out men and women who knew better. . . . Trump’s favorite pillowy-haired congressmen—fresh off their Fox “hits”—greeting the various Spicers, Kellyannes, and other C-listers who were bumped temporarily up to B-list status by their White House entrée.

But the guests who stood out for me most were Republican House Leader Kevin McCarthy and the busybody senator from South Carolina, Lindsey Graham. I would sometimes see them around the lobby or steakhouse or function rooms, skipping from table to table and getting thanked for all the wonderful things they were doing to help our president. They had long been among the most supplicant super-careerists ever to play in a city known for the breed, and proved themselves to be essential lapdogs in Trump’s kennel.

Graham remains perhaps Trump’s closest collaborator in the Senate, a frequent golf partner and nuanced handler of the presidential ego. This week, he was subpoenaed as part of an investigation into election meddling. He might now have to testify about what exactly he was trying to do when he called Georgia’s secretary of state wondering whether he really needed to count all those mail-in votes.

I will admit I never loved the Trump story. This sometimes surprises people. I have been covering Washington for many years; I’ve been accused of being a “keen observer” of the capital. Surely, I must have been thrilled to have such a ridiculous piece of work at the center of it all, right?

Trump said and did obviously awful and dangerous things—racist and cruel and achingly dumb and downright evil things. But on top of that, he is a uniquely tiresome individual, easily the sorest loser, the most prodigious liar, and the most interminable victim ever to occupy the White House. He is, quite possibly, the biggest crybaby ever to toddle across history’s stage, from his inaugural-crowd hemorrhage on day one right down to his bitter, ketchup-flinging end.

Better objects of our scrutiny—and far more compelling to me—are the slavishly devoted Republicans whom Trump drew to his side. It’s been said before, but can never be emphasized enough: Without the complicity of the Republican Party, Donald Trump would be just a glorified geriatric Fox-watching golfer. I’ve interviewed scores of these collaborators, trying to understand why they did what they did and how they could live with it. These were the McCarthys and the Grahams and all the other busy parasitic suck-ups who made the Trump era work for them, who humored and indulged him all the way down to the last, exhausted strains of American democracy.

The GOP’s shame, ongoing, is underscored by the handful of brave Republicans willing to speak the truth about Trump in public, before the January 6 committee and on the panel itself. The question now is whether they have any hope of wresting some admirable remnant of their party back from Trump’s abyss before he wins the Republican nomination for president in 2024 or, yes, winds up back in the White House.

Nearly a decade ago I wrote a book about Washington at its (seemingly) grossest and most decadent. This Town, the book was called, and it portrayed the pre-Trump capital as a feudal village of operatives, former officeholders, minor celebrity journalists, and bipartisan coat holders. Democrats and Republicans kept coming to Washington, vowing change, only to get co-opted, get richer, and never leave.

People now toss around phrases like fundamental threat to democracy and civil war, and they don’t necessarily sound overheated. Deference to power in service to ambition has always been a Washington hallmark, but Trump has made the price of that submission so much higher.

Consider again the doormat duo—McCarthy and Graham. I’ve known both men for years, at least in the weird sense that political reporters and pols “know” each other. They are a classically Washington type: fun to be around, starstruck, and desperate to keep their jobs or get better ones—to maximize their place in the all-important mix. On various occasions I have asked them, in so many words, how they could sidle up to Trump like they have. The answer, basically, is that they did it because it was the savviest course; because it was best for them. If Trump had one well-developed intuition, it was his ability to sniff out weakness in people . . . . People like McCarthy and Graham benefited a great deal from making it work with Trump, or “managing the relationship,” as they say.

McCarthy knew that alienating Trump would blow up any chance he had of becoming speaker, which had become the singular objective of his “public service,” such as it was. . . . . But “managing the relationship” was often a daily struggle, McCarthy conceded, when I interviewed him for The New York Times in his Bakersfield, California, district in April 2021. “He goes up and down with his anger,” McCarthy said of Trump. “He’s mad at everybody one day. He’s mad at me one day … This is the tightest tightrope anyone has to walk.”

Once, early in 2019, I asked Graham a version of the question that so many of his judgy old Washington friends had been asking him. How could he swing from being one of Trump’s most merciless critics in 2016 to such a sycophant thereafter? I didn’t use those exact words, but Graham got the idea. “Well, okay, from my point of view, if you know anything about me, it’d be odd not to do this,” he told me. “‘This,’” Graham specified, “is to try to be relevant.” Relevance: It casts one hell of a spell.

There was always a breathless, racing quality to both men’s voices when they talked about the thrill ride of being one of Trump’s “guys.”

What would you do to stay relevant? That’s always been a definitional question for D.C.’s prime movers, especially the super-thirsty likes of McCarthy and Graham. If they’d never stooped this low before, maybe it’s just because no one ever asked them to.

How do you sleep at night? Trump’s protectors were always being tormented by this nuisance question. What will future historians think about how you’ve conducted yourself? was another. Do you ever think about your … you know … legacy?

Early on, when wary Republicans were still publicly dreading where the Trump experiment might lead, you’d hear flashes of concern over how it—or they—might be adjudicated by those ever-hovering future historians. As his own presidential campaign was ending in 2016, Marco Rubio predicted that there would one day be a “reckoning” inside the GOP. . . . . (Update: Rubio cleaned up his act, became a stalwart Trump patron, and we’re still waiting on that reckoning.)

“My attitude about my legacy is: Fuck it,” Rudy Giuliani told New York magazine’s Olivia Nuzzi in 2019 (his fly was unzipped at the time and he was drunk on Bloody Marys, per Nuzzi). Other versions were a bit more erudite. “Everyone dies,” Attorney General William Barr rhapsodized to CBS’s Jan Crawford in 2019. “I don’t believe in the Homeric idea that immortality comes by, you know, having odes sung about you over the centuries.”

I met with McCarthy in the spring of 2021 in a Bakersfield dessert joint . . . I tossed the pesky “legacy” question his way. . . . McCarthy kept his head down and pulled up a photo of the pope. . . . . “Here’s another of me with Trump on Air Force One,” McCarthy said. Then: “What did you ask me again?”

I repeated the question, suggesting that there might be far-reaching ramifications for his continued propping-up of Trump. McCarthy eventually looked up. “Oh, the Jeff Flake thing?” he said. No one’s putting up any statues to Flake at the Capitol, he pointed out

The response is worth unpacking, if only to underscore how dismissive McCarthy was of any suggestion that his conduct could bear historic weight beyond the day-to-day expediencies of keeping Trump’s favor. Flake and Sanford were both principled conservatives whose convictions were tested and affirmed over long careers. They freely condemned Trump throughout his rise, which led to inevitable abuse from the White House, pariah status within their party, and cancellation by “the base.” . . . . Republican colleagues would often praise Flake and Sanford for their courage and principles—but only privately.

“My legacy doesn’t matter,” Trump told his longtime aide Hope Hicks a few days after the 2020 election, according to an account in Peril, by Bob Woodward and Robert Costa. “If I lose, that will be my legacy.” This became the essential ethos of Republican nihilism. By lashing themselves so tightly to Trump, Republicans could act as if the president’s impunity and shamelessness extended to them. His strut of cavalier disregard became their own.

“Don’t care,” I overheard Graham say in early 2020 to a reporter on the Capitol subway platform who asked him whether his reputation had suffered because of his association with Trump. . . . “I don’t care if they have to stay in these facilities for 400 days,” Graham said on Fox News, about the hundreds of migrant children who had been separated from their parents and locked in cages.

No Republican spoke with more contempt for Trump during the 2016 primaries than Graham did. He called him a “complete idiot,” and “unfit for office,” among other things. But then Trump became president and deemed Graham fit to play golf with him. Suddenly Graham was getting called a “presidential confidant.”

The arrangement also proved “helpful” to Graham’s goal of continuing to represent deep-red South Carolina in the U.S. Senate. It got him into the clubhouse. It kept him fed and employed and on TV.

But Graham’s dash from McCain to McCain’s arch nemesis made him a kind of alpha lapdog. Old friends kept asking, “What happened to Lindsey?” . . . . Any ambivalence Graham had over Trump’s conduct—for example, trashing his best friend [John McCain] to the grave and beyond—was buried by the fairy dust of relevance.

McCain was never shy about voicing his low opinion of Trump, but what was really eating at him then was how readily so many of his Republican colleagues continued to abase themselves before [Trump]

the president. “It comes down to self-respect,” McCain kept saying. He also noted that a big reason Trump remained so popular with GOP voters was because most of their putative “leaders” were too afraid to defy him. “Republicans who could shape opinion just keep sucking up to the guy,” he told me.Watching the procession of GOP genuflectors, I was reminded of Susan Glasser’s 2019 profile of Secretary of State Mike Pompeo in The New Yorker, in which she quoted a former American ambassador describing Pompeo as “a heat-seeking missile for Trump’s ass.” This image stuck with me (unfortunately) and also remained a pertinent descriptor for much of the Republican Party long after said ass had been re-homed to Florida.

Like Vladimir Putin, Trump will take what people let him take. He will do what he can get away with. The courage and character of Ukraine stands in perverse contrast to America’s cowering Republican Party, whose resistance might as well have been led by the Uvalde police.

Liz Cheney, who spent years studying and working in countries with autocratic regimes in Eastern Europe and the Middle East, has made it clear that she believes the primary existential threat to America today resides within her own political party.

Friday, July 08, 2022

The New American Exceptionalism: Minority Rule

If a woman in Texas has an abortion she is breaking the law, even if her pregnancy is the result of a rape. The same woman may, however, buy an ar-15 rifle capable of firing 45 rounds a minute, and she may carry a pistol on her hip when picking her toddler up from pre-school. In these, and in a few other ways, America is an outlier compared with other rich democracies. You might assume that this simply reflects the preferences of voters. You would be wrong: it is the result of a political failure.

American exceptionalism once seemed to be the cause of all sorts of transatlantic differences, for good and ill. America’s greater religiosity explained the intensity of the culture wars over gay marriage and abortion. Greater individualism explained the dynamism of America’s entrepreneurial economy, the willingness to move in search of something better and also, unfortunately, the passion for guns.

This diagnosis is no longer accurate. Before covid-19 hit, internal migration was at its lowest since records began. The share of Americans who belong to a church, synagogue or mosque has fallen from 70% in 2000 to below 50% now. The birth rate is the same as in France.

As America has become less exceptional in these ways, so has its public opinion. On abortion, Americans’ views are strikingly close to those in other rich countries. A majority of Americans think it should be legal in the first trimester and restricted thereafter, with exemptions if the mother’s health is at risk, and for rape and incest—a qualifier that should be redundant, but is included because six Republican state legislatures have abortion bans with no such exemptions. Support for gay marriage, at 40% in 2000, is at 70% now. Americans are about as accepting of homosexuality as Italians are, and more tolerant than the Japanese or Poles.

On climate change, American attitudes are remarkable in their ordinariness. Three-quarters of Americans are willing to make some changes to their lives to help reduce the effects of climate change. That is slightly higher than the share of Dutch who say the same, and about level with Belgium. On guns, America truly is an outlier: it is the only country with more civilian-owned firearms than people. But here too the overall picture is misleading: 60% of American homes have no guns in them, up from 50% in 1960. A clear majority favours banning guns that can fire lots of bullets quickly.

Yet despite this, America has not banned assault weapons, nor legalised abortion or gay marriage through the normal democratic process.

Yet despite this, America has not banned assault weapons, nor legalised abortion or gay marriage through the normal democratic process. Ireland, where anti-abortion sentiment has historically been stronger, has come to a democratic settlement on abortion—as has Japan, where a woman’s right to choose is less popular than in America. Switzerland, nobody’s idea of a forward-thinking place (it gave women the right to vote only in 1971), has legalised gay marriage through a referendum. America and Italy are the only members of the g7 that have not enshrined net-zero emissions targets in law.

America has been unable to settle any of these questions through elections and votes in legislatures. The federal right to abortion was created by the Supreme Court in 1973. The closest thing to a national climate law came in 2007 when the Court decided the president could regulate carbon emissions. Then in 2015 the Court decided gay marriage was a constitutional right. In all three cases the Court stepped in when Congress had failed to legislate. Now that the Court has reversed one of those decisions and some justices are talking about undoing the others, the costs of this political abdication are ever more apparent.

The solution sounds easy: Congress should pass laws that reflect public opinion. In practice, assembling a House majority, 60 votes in the Senate and a presidential signature for anything vaguely controversial is extraordinarily hard. The result is a set of federal laws that do not reflect what Americans actually want. That is what is exceptional now.

Thursday, July 07, 2022

The Current GOP is Beyond Rescue

In 1991, the last president of the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev, was briefly deposed in a coup by hard-line members of the Soviet Communist Party. Gorbachev, upon his return to Moscow, tried to differentiate between the plotters and the Party itself. One of his closest advisers, Aleksandr Yakovlev, told him that this effort was pointless, akin to “serving tea to a corpse.”

Republicans such as Senator Mitt Romney—an honorable man for whom I voted in 2012—and a handful of others in the GOP, including Liz Cheney and Adam Kinzinger, should take note of Yakovlev’s phrase. Over the weekend, The Atlantic published a plea from Senator Romney for Americans “across the political spectrum” to stop ignoring “potentially cataclysmic threats.” The senator from Utah is right to be worried about the detachment of so many Americans. But Romney, Cheney, and Kinzinger cannot rescue their party, either—at least not in its current form.

In fact, I wonder if the Republicans can ever return to being the kind of party that once nominated someone like Mitt Romney for the American presidency. I say this not because of Donald Trump, nor as the apostate Republican I am. . . . . I say this not because I disagree with the Republicans on many policy issues; I do, but as a New England Republican who identified with (and worked for) moderates of a bygone era, I have always had differences with the hard-right social conservatives.

Rather, I say this because millions of Republicans seem to have irreversibly lost touch with reality itself. Senator Romney, for his part, seems to share this concern, but he softens this criticism of his own side . . . .

But as the old song from Sesame Street goes: One of these things is not like the other. Unfounded optimism about droughts or recessions is one thing; it’s another thing entirely to embrace the idea that an insurrection and an attack on the Capitol was conducted by agents of the United States government itself.

Other Republicans have blown past such pedestrian crackpottery and now have escaped the last tendrils of Earth’s gravity.

The Republican candidate for secretary of state in Michigan, for example, believes that people can transmit demonic possession through “intimate relations,” according to CNN. Meanwhile, Pennsylvania Republicans have nominated a candidate for governor, Doug Mastriano, who has implied that he might invalidate any election result he doesn’t like in 2024—and that’s probably the least disturbing thing about him. As Jonathan Last put it recently, the Democratic nominee, Josh Shapiro, is an ordinary politician, while Mastriano “is an insane person. A seditionist. A Christian nationalist. A conspiracy nut.”

Almost every other national Republican is either silent or on board with the dark fantasies and deepening paranoia that now rule the GOP. For example, Representative Elise Stefanik of New York, the relentlessly ambitious third-ranking House Republican, endorsed the developer Carl Paladino for a newly redistricted House seat in the state; in 2021 Paladino said that Adolf Hitler was “the kind of leader we need.”

When Senator Ron Johnson, of Wisconsin, is paddling about in the anti-vaccine fever swamps, and Senate candidate J.D. Vance is cozying up to people like the congressional conspiracy theorist Marjorie Taylor Greene and the execrable Matt Gaetz, what exactly counts as “going rogue” and how can anyone distinguish it from just another day in the Republican Party?

In the end, despite the efforts of Senator Romney and other reasonable Republicans, the fringe is now the base. The last rational members of the GOP—both elected and among the rank and file—need to speak even harsher truths to their own people, as Liz Cheney did last week at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library. Otherwise, the madness will spread, and our institutions will continue an accelerating slide into a nightmare that will engulf all Americans, regardless of party.

Wednesday, July 06, 2022

Mass Shootings: A Nation of Hostages

At the start of a different week, I might have written about many things, including politics. But not today. Instead, I am watching a group of my fellow citizens deal with a slaughter of defenseless people on a summer day at a parade.

We do not yet know why a shooter opened fire on a crowd in Illinois yesterday. Given what we know about the suspected killer, I think it is unlikely that the massacre in Highland Park was part of an organized terror plot, but rather yet another case of a young male loser attacking his own community. Nonetheless, the effect of these mass shootings is the same as terrorism: They rob us of a general sense of safety and turn us into a nation of hostages.

In the first few weeks after the 9/11 attacks, I traveled to London and New York. That’s when I realized that the terrorists had succeeded in making an ordinary citizen—me—think about terrorism constantly. I wondered, on my first trips back to those cities and during almost every visit to any metropolis for a few more years: Am I here on the wrong day? Is this the site of the next attack? . . . . . Americans now have to feel this way all the time, in their own country, at almost any mass gathering, in even the quiet towns and suburbs that people once thought of as relatively immune to such terrifying events.

Such feelings are corrosive and depressing. They undermine our faith in our system of government. (This is often the goal of terrorist violence.) Worse, mass shootings undermine our faith in one another. And that loss of faith leads me to a thought I cannot escape: There is nothing we can do about such events. They will keep happening.

This is not because I am a pessimist. . . . . But when it comes to this particular kind of violence—a lone shooter attacking a community with a powerful weapon—all of the foundations for another disaster are already in place. A bizarre gun culture created the demand for millions of guns; an extremist lobby has attacked almost every measure to place any restrictions on those guns. (And the Supreme Court seems determined to roll back any limits on the ability of states to control access to these weapons.)

Add to this the final and necessary element: a group of young males who are determined to take their frustrations or delusions or fantasies out on others.

So what can we do?

We can choose not to despair. We can, as an act of will, keep faith in our society and our institutions. Just as we do not give up on living when we are ill, we cannot give up on ourselves because of these monstrous acts. We can do this concretely by demanding more changes to our laws, but we can also exert social pressure on an irresponsible gun culture. After all, we managed as a nation to make smoking a legal but socially unacceptable habit in everything from movies to public spaces. Do we really think we can’t collectively start pushing back against gun culture the same way?

This sounds anodyne, almost ridiculous, on a day like this. The guns will not disappear and another such attack is a near certainty. But we can and must try to mitigate the danger—and the damage to our democracy—by refusing to surrender to the anguish, by insisting that our fellow citizens come to their senses, and by affirming our faith that a great democracy can heal itself from even the most grievous wounds.

Those in the gun culture need to become social outcasts and insurance companies need to start refusing to insure homes with guns and/or make premiums extremely expensive so that gun cultists will have to decide whether they want their guns or their homes (most mortgages require insurance, after all).

Tuesday, July 05, 2022

Christian Nationalists Are Excited About What Comes Next

The shape of the Christian nationalist movement in the post-Roe future is coming into view, and it should terrify anyone concerned for the future of constitutional democracy.

The Supreme Court’s decision to rescind the reproductive rights that American women have enjoyed over the past half-century will not lead America’s homegrown religious authoritarians to retire from the culture wars and enjoy a sweet moment of triumph. On the contrary, movement leaders are already preparing for a new and more brutal phase of their assault on individual rights and democratic self-governance. Breaking American democracy isn’t an unintended side effect of Christian nationalism. It is the point of the project.

A good place to gauge the spirit and intentions of the movement that brought us the radical majority on the Supreme Court is the annual Road to Majority Policy Conference. At this year’s event, which took place last month in Nashville, three clear trends were in evidence. First, the rhetoric of violence among movement leaders appeared to have increased significantly from the already alarming levels I had observed in previous years. Second, the theology of dominionism — that is, the belief that “right-thinking” Christians have a biblically derived mandate to take control of all aspects of government and society — is now explicitly embraced. And third, the movement’s key strategists were giddy about the legal arsenal that the Supreme Court had laid at their feet as they anticipated the overturning of Roe v. Wade.

They intend to use that arsenal — together with additional weaponry collected in cases like Carson v. Makin, which requires state funding of religious schools if private, secular schools are also being funded; and Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, which licenses religious proselytizing by public school officials — to prosecute a war on individual rights, not merely in so-called red state legislatures but throughout the nation.

Democrats, they said, are “evil,” “tyrannical” and “the enemy within,” engaged in “a war against the truth.”

“The backlash is coming,” warned Senator Rick Scott of Florida. “Just mount up and ride to the sounds of the guns, and they are all over this country. It is time to take this country back.”

Lt. Gov. Mark Robinson of North Carolina said, “We find ourselves in a pitched battle to literally save this nation.” Referencing a passage from Ephesians that Christian nationalists often use to signal their militancy, he added, “I don’t know about you, but I got my pack on, I got my boots on, I got my helmet on, I’ve got on the whole armor.”

It is not a stretch to link this rise in verbal aggression to the disinformation campaign to indoctrinate the Christian nationalist base in the lie that the 2020 election was stolen, along with what we’re learning from the Jan. 6 hearings. The movement is preparing “patriots” for the continuation of the assault on democracy in 2022 and 2024.

The intensification of verbal warfare is connected to shifts in the Christian nationalist movement’s messaging and outreach, which were very much in evidence at the Nashville conference.

Seven Mountains Dominionism — the belief that “biblical” Christians should seek to dominate the seven key “mountains” or “molders” of American society, including the government — was once considered a fringe doctrine, even among representatives of the religious right. At last year’s Road to Majority conference, however, there was a breakout session devoted to the topic. This year, there were two sessions, and the once arcane language of the Seven Mountains creed was on multiple speakers’ lips.

The hunger for dominion that appears to motivate the leadership of the movement is the essential context for making sense of its strategy and intentions in the post-Roe world.

Movement leaders have also made it clear that the target of their ongoing offensive is not just in-state abortion providers, but what they call “abortion trafficking” — that is, women crossing state lines to access legal abortions, along with people who provide those women with services or support, like cars and taxis. Mrs. Youman hailed the development of a new “long-arm jurisdiction” bill that offers a mechanism for targeting out-of-state abortion providers. “It creates a wrongful death cause of action,” she said, “so we’re excited about that.”

Americans who stand outside the movement have consistently underestimated its radicalism. But this movement has been explicitly antidemocratic and anti-American for a long time.

It is also a mistake to imagine that Christian nationalism is a social movement arising from the grassroots and aiming to satisfy the real needs of its base. It isn’t. This is a leader-driven movement. The leaders set the agenda, and their main goals are power and access to public money. They aren’t serving the interests of their base; they are exploiting their base as a means of exploiting the rest of us.

Christian nationalism isn’t a route to the future. Its purpose is to hollow out democracy until nothing is left but a thin cover for rule by a supposedly right-thinking elite, bubble-wrapped in sanctimony and insulated from any real democratic check on its power.

Monday, July 04, 2022

How to Restrain an Out of Control Supreme Court

Last December, during oral arguments in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the case in which the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, Justice Sonia Sotomayor noted that “there’s so much that’s not in the Constitution, including the fact that we have the last word. Marbury versus Madison. There is not anything in the Constitution that says that the Court, the Supreme Court, is the last word on what the Constitution means. It was totally novel at that time. And yet, what the Court did was reason from the structure of the Constitution that that’s what was intended.”

It was a remarkable observation. Sotomayor’s primary intent was to argue that rights and prerogatives need not be explicitly delineated in the Constitution for them to exist. The right to privacy — more specifically, the right to terminate a pregnancy — does not appear anywhere in the document, but neither does the Supreme Court’s power of judicial review. Both exist by strong implication.

It’s an observation worth revisiting. . . . Six conservative justices, enjoying life tenure on the bench, are fundamentally reshaping the very meaning of citizenship. Their power to do so is seemingly absolute and unchecked.

Liberal critics of today’s judicial activism are right when they note that the Supreme Court essentially arrogated to itself the right of judicial review — the right to declare legislative and executive actions unconstitutional — in 1803, in the case of Marbury v. Madison. There is nothing in the Constitution that confers this power upon the only unelected branch of government.

But that doesn’t make the court more powerful than the executive and legislative branches. Acting in concert, the president and Congress may shape both the size and purview of the court. They can declare individual legislative measures or entire topics beyond their scope of review. It’s happened before, notably in 1868, when Congress passed legislation stripping the Supreme Court of its jurisdiction over cases related to federal writs of habeas corpus. In the majority decision, Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase acknowledged that the court’s jurisdiction was subject to congressional limitation. Subsequent justices, over the past century, have acknowledged the same.

That’s the brilliance of checks and balances. In the same way that Congress or the Supreme Court can rein in a renegade president, as was the case during Watergate, the president and Congress can place checks on an otherwise unconstrained court, if they believe the justices have exceeded their mandate.

It’s clear from the record that the men who wrote the Constitution intended the Supreme Court, and the lower federal courts, to enjoy a constitutional veto over acts of Congress and of the states.

But they did not intend this power to be unchecked or unlimited.

By now, it’s well-known that Congress can change the size, and thus the composition, of the Supreme Court by simple legislation. Court-packing, as it’s been called since 1937, when President Franklin Roosevelt unsuccessfully attempted to circumvent a hostile court by expanding its membership, is a deeply controversial practice.

Critically, but less widely understood, the Constitution also grants Congress the power to strip the Supreme Court of its jurisdiction over specific matters.

In theory, Congress could very easily pass legislation denying the Supreme Court jurisdiction over a new voting rights act, a law codifying the right to privacy (including abortion rights), and other popular measures. If they so chose, Congress and the president could go further, reducing the court to a shell of its former self, leaving it to adjudicate minor matters of little significance. Of course, with the filibuster in place, this outcome is about as likely as a bill expanding the court’s membership, which is to say, very unlikely.

Ultimately, it is the responsibility and prerogative of the executive and legislative branches to encourage greater restraint and humility on the part of the judiciary.

Judicial review is well-rooted in American political tradition. But so are checks and balances. To save the Supreme Court from itself, Congress might first have to shrink it.

How To Fix America's Broken Democracy

As we celebrate the Fourth of July, views of the Founding Fathers are more polarized than ever before. Some progressives want to tear down their monuments, because so many of the Founders were slave-holders, and they created a political system that denied political rights to women and minorities. Most conservatives, by contrast, still view the Founders as demigods and seek to squelch any criticism of them in public schools — promoting a spirit of conformity utterly alien to a founding generation that joyously engaged in never-ending disputation.

More than that, conservative jurists who extol the theory of “originalism” insist that the only way to interpret the Constitution is according to the way the Founders themselves viewed it. The Supreme Court has just upheld abortion restrictions and struck down gun restrictions based on the dubious claim to be channeling the Constitution’s drafters, even though many historians disagree with the right-wing interpretations.

Is there a sensible middle ground between vituperation and veneration of the Founders? Yes. We should acknowledge their manifold faults, while also paying tribute to their still-radical vision of a world in which everyone has an “unalienable” right to “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” Above all, we must vindicate their desire to create a “more perfect Union” to “secure the Blessings of Liberty.”

For all their blind spots, the Founders created a mechanism whereby the original imperfections of the Constitution could be fixed over time. Two mechanisms, actually.

First, the constitutional amendment process. This enabled a “new birth of freedom” after the Civil War, with amendments to abolish slavery and grant civil rights to African Americans, and again after World War I, with an amendment giving women the vote.

Second, the Founders created a Supreme Court that had the ultimate power to interpret — or reinterpret — the often-opaque articles of the Constitution. This allowed the court of the 1930s, after initial resistance, to ratify the creation of a rudimentary welfare state, and the court of the 1950s and 1960s to strike down school segregation and expand rights of privacy that are now under attack.

The United States of America would not have survived this long if we had not done so much to modify the original Constitution and the way it was interpreted in the republic’s early days. In particular, we have greatly scaled back the pernicious doctrine of “state’s rights” that too often has been a cover for the supremacy of a few powerful white men. . . . . Unfortunately, we are now walking back into the darkness. Because of a benighted Supreme Court, 40 million women are about to lose their reproductive freedom.

Most of the Founders knew better than to try to shackle their progeny to their own worldview. Thomas Jefferson rejected the tendency to “look at constitutions with sanctimonious reverence, and deem them like the arc of the covenant, too sacred to be touched.” He argued “that laws and institutions must go hand in hand with the progress of the human mind. As that becomes more developed, more enlightened, as new discoveries are made, new truths disclosed, and manners and opinions change with the change of circumstances, institutions must advance also, and keep pace with the times.”

[O]ur institutions do need to be significantly reformed to “keep pace with the times.”

There is no justice in a political system that gives Republicans six of nine Supreme Court seats even though a Republican has won the popular vote for president only once in the past 30 years. So, too, there is something deeply amiss with a Senate that gives California (population 39.3 million) the same number of seats as Wyoming (population 581,348). The Founders never envisioned such an imbalance between power and population. It undermines any pretense that we are still a democracy.

We should abolish the electoral college and make the election of senators proportional to population. Let the will of the people prevail. We should – but we won’t. Small states will block any constitutional amendment that would strip them of their outsize power.

We should, for example, expand the House of Representatives and the Supreme Court. They reached their present size in 1912 and 1869, respectively, when the country was far smaller. (The U.S. population has tripled in the past century.) We should also end the Senate filibuster, whose use has dramatically expanded in recent years, creating a de facto supermajority requirement that gives a small minority of the population a veto over all legislation.

Instead of acrimoniously and endlessly debating whether the Founders were good or bad, let’s focus on improving the system they created so that it better serves Americans in the 21st century. As Jefferson knew, “institutions must advance” along with society.

Will any of these curative measures come to pass? Frighteningly, probably not and the nation will lurch closer to falling apart.

Sunday, July 03, 2022

The Courage of Cassidy Hutchinson

Americans learned something shocking from Cassidy Hutchinson’s testimony to the January 6th committee this week, but it was not about Donald Trump. The fact that the 45th president is vile and corrupt was clear long before he won the Republican nomination in 2016. What was more remarkable about the 26-year-old former White House aide’s account of events before and during the Capitol Hill riot was that someone so embedded in Trumpworld had the moral compass to provide it.

Matter-of-factly, Ms Hutchinson described overhearing Mr Trump being informed that the maga crowd had guns and in response suggesting it be allowed to keep them. That was before he instructed its members to go to the Capitol and “fight like hell”. She told the committee that she heard Mr Trump had to be restrained by his security detail after he tried to lead the mob there. No one with her proximity to the president had broken ranks so devastatingly. Even though, as she made clear, senior Trump courtiers had known perfectly well what Mr Trump was up to. She recalled Mark Meadows, the chief of staff, warning that “things might get real, real bad on January 6th.” She described Pat Cipollone, the White House counsel, advising against Mr Trump’s plan to march to the Capitol because “we’re going to get charged with every crime imaginable if we make that movement.” So far both men have refused to testify to the committee.

This embrace of the unconscionable by millions of otherwise reasonable Americans is by far the biggest novelty of the Trump era. By comparison, the paranoia and bigotry of the Capitol Hill rioters was old hat. Around a quarter of Americans have always expressed such sentiments. They represent the “paranoid style” in American politics described by the sociologist Richard Hofstadter . . . . The current eruption, Mr Trump’s maga base, represents around half the Republican coalition. Yet the real puzzle is why the other half, including amiable conservatives up and down the country, have gone along with it.

Economic privation was an early explanation—which never squared with the gleaming trucks parked outside Mr Trump’s rallies. Disinformation and racism were more convincing suggestions, but insufficient. Many Republicans knew all along what Mr Trump was . . . . Swathes of white America are resentful and fearful of diversity, rampant liberalism and other big ways in which America is changing, which they blame on the left. This cultural outlook has become the main difference between the two parties. Whereas Democrats are positive about America’s multiracial future, most Republicans say the country is “in danger of losing its culture and identity”.

Provided Mr Trump can be stopped, which seems likelier than not, it is in theory easy to think that the right will return to sanity. Yet the reality looks darker, partly because of the structural advantages that are sparing Republicans the electoral reckoning their dalliance with Mr Trump merits. Republicans are getting more power than the Democrats through the electoral college and Senate with fewer votes. And they were successfully compounding that undemocratic edge through all manner of ways to defy the majority, from judicial activism to gerrymandering, even before Mr. Trump took it a stage further by trying to steal an election.

Among scholars of democracy it has become a truism to predict that America’s will get worse before it gets better. It is hard to disagree. Even without Mr Trump, culture warring will dominate conservatism until Republicans can no longer win power by it. That is why Governor Ron DeSantis of Florida, Mr Trump’s closest rival, is spending so much time banning critical race theory and references to single-sex marriage in schools. Yet it is important, in what looks bound to be a protracted battle, to at least celebrate tactical successes—like Ms Hutchinson’s brave performance on the Hill this week. America needs an awful lot more conservative heroes like her.

Will SCOTUS's Deference to Religion Come Back to Bite It?

|

| (Illustration by João Fazenda) |

The lasting depredations of the Trump Presidency were brought into sharp focus by last week’s testimony before the House Select Committee investigating the events of January 6th, which left an indelible portrait of Donald Trump as a food-throwing despot willing to encourage an armed mob to march to the Capitol. And, in addition to an attempted coup, we have him to thank for 2022’s becoming the turning point of the Supreme Court’s conservative revolution.

In a single week in late June, the conservative Justices asserted their recently consolidated power by expanding gun rights, demolishing the right to abortion, blowing a hole in the wall between church and state, and curtailing the ability to combat climate change. The Court is not behaving as an institution invested in social stability, let alone in the importance of its own role in safeguarding that stability. But what if its big and fast moves, eviscerating some constitutional rights and inflating others, are bound for collision? As people harmed by one aspect of its agenda look to other aspects of it to protect them, the Court may not be altogether pleased with where that process leads.

Shortly before the Court, in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, overruled Roe v. Wade, a synagogue filed suit in a Florida court, challenging, under the Florida constitution, the state’s new law criminalizing pre-viability abortions. Among the plaintiff’s claims is that the abortion ban violates the right of Jews “to freedom of religion in the most intimate decisions of their lives.” The suit states that Jewish law stipulates that life begins at birth, not before, and “requires the mother to abort the pregnancy” if there is a risk to her “health or emotional well being.” Thus, the plaintiff argues, the abortion ban infringes on Jewish free exercise of religion.

Many post-Dobbs lawsuits can also now be expected to assert that abortion bans violate state constitutions, which may be more protective of individual rights than the federal Constitution is. Marriage equality, for example, was protected in Massachusetts by a state constitutional ruling twelve years before the Supreme Court declared a federal constitutional right to same-sex marriage.

But the Jewish group’s claim is a bellwether, because the Supreme Court has lately been exceedingly accommodating of people’s religious views. This term, two cases resulted in historic expansions of the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment. The Court held that Maine, which provides tuition funds for students who reside in districts lacking public secondary schools to attend secular schools elsewhere, must also provide funds for such students who choose to attend religious schools. The Court also held, in the case of a football coach at a public high school in Washington State, who knelt and prayed on the field after games, that the school district could not stop him, even if it wanted only to avoid the appearance of endorsing religion. . . . And, in a free-speech case this term, the Court held that Boston must allow a group to fly a Christian flag on the flagpole outside city hall if it allows other groups to hoist non-religious flags, such as the pride flag.

The Supreme Court’s expansion of religious liberty is long-running, but it has rapidly accelerated in the two years since the Court gained a conservative supermajority. At the start of the pandemic, in 2020, the Court repeatedly rejected claims of churches that objected to states’ stay-at-home orders. But, after Justice Amy Coney Barrett was confirmed, in the fall of 2020, a majority—the same five conservative Justices who eventually voted to overrule Roe v. Wade—held in favor of Catholic and Orthodox Jewish organizations that objected to a state’s stricter capacity limit for houses of worship than for essential businesses.

According to a recent Yale Law Journal study conducted by Zalman Rothschild, a fellow at the Stanford Constitutional Law Center, . . . . “free exercise has exploded out of proportion.” Indeed, that expansion threatens to allow people to claim a religious free-exercise right to discriminate against L.G.B.T.Q. individuals. But it may also arm those who seek religious exemptions from abortion bans with powerful arguments that courts will have to grapple with. And some groups that make such arguments may be beyond the embrace of the general public—much less that of Republican-dominated courts.

The Satanic Temple, for example, headquartered in Salem, Massachusetts, claims seven hundred thousand registered members in congregations around the world. Courts and the I.R.S. have recognized the organization as a religion (which doesn’t actually worship Satan as a deity but, instead, views him as a symbol of dissent against tyrannical authority). In keeping with one of its core tenets—that “one’s body is inviolable, subject to one’s own will alone”—TST has filed several lawsuits pressing a free-exercise claim that objects to abortion bans. Its position is that a state’s imposition of a waiting period or counselling prior to an abortion is as much a violation of religious freedom as it would be prior to a baptism or a Communion.

It is possible that these free-exercise claims won’t succeed, because avoidance of hypocrisy is not a value that we expect from this Supreme Court, any more than we expect it from the man responsible for its composition. The Select Committee and the Department of Justice may yet force Trump to answer for some of his actions, but, notwithstanding the historic swearing-in of Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson last week, we are stuck with his Court, and the damage it will do, for the next generation.

Again, my guess is the zealots and hypocrites on the Court will ultimately show that only right wing Christianity will be afforded deference uder their agenda.