|

| Image by Gabriel Carr |

When he wasn’t melting down over how “very badly” he was treated or acting like a seditious lunatic, Donald Trump could be downright serene in certain Washington settings—and never more so than when he would swan in for dinner at the Trump International Hotel, a few blocks down Pennsylvania Avenue from the White House and the only other place where he would ever agree to eat.

Unlike the Obamas, who would sneak out for date nights at trendy restaurants, Trump was hardly discreet when he went out to dinner. For Trump, a big, applauded entrance was as essential to the experience as the shrimp cocktail, fries, and 40-ounce steak. Each night, assorted MAGA tourists and administration bootlickers would descend on the atrium bar on the small chance they’d get to glimpse Trump himself in his abundant flesh . . . .

Lots of Washington reporters would hang around the establishment, too. We could always pick up dirt that Trump and his groveling legions tracked in. The place was crawling with them, these hollowed-out men and women who knew better. . . . Trump’s favorite pillowy-haired congressmen—fresh off their Fox “hits”—greeting the various Spicers, Kellyannes, and other C-listers who were bumped temporarily up to B-list status by their White House entrée.

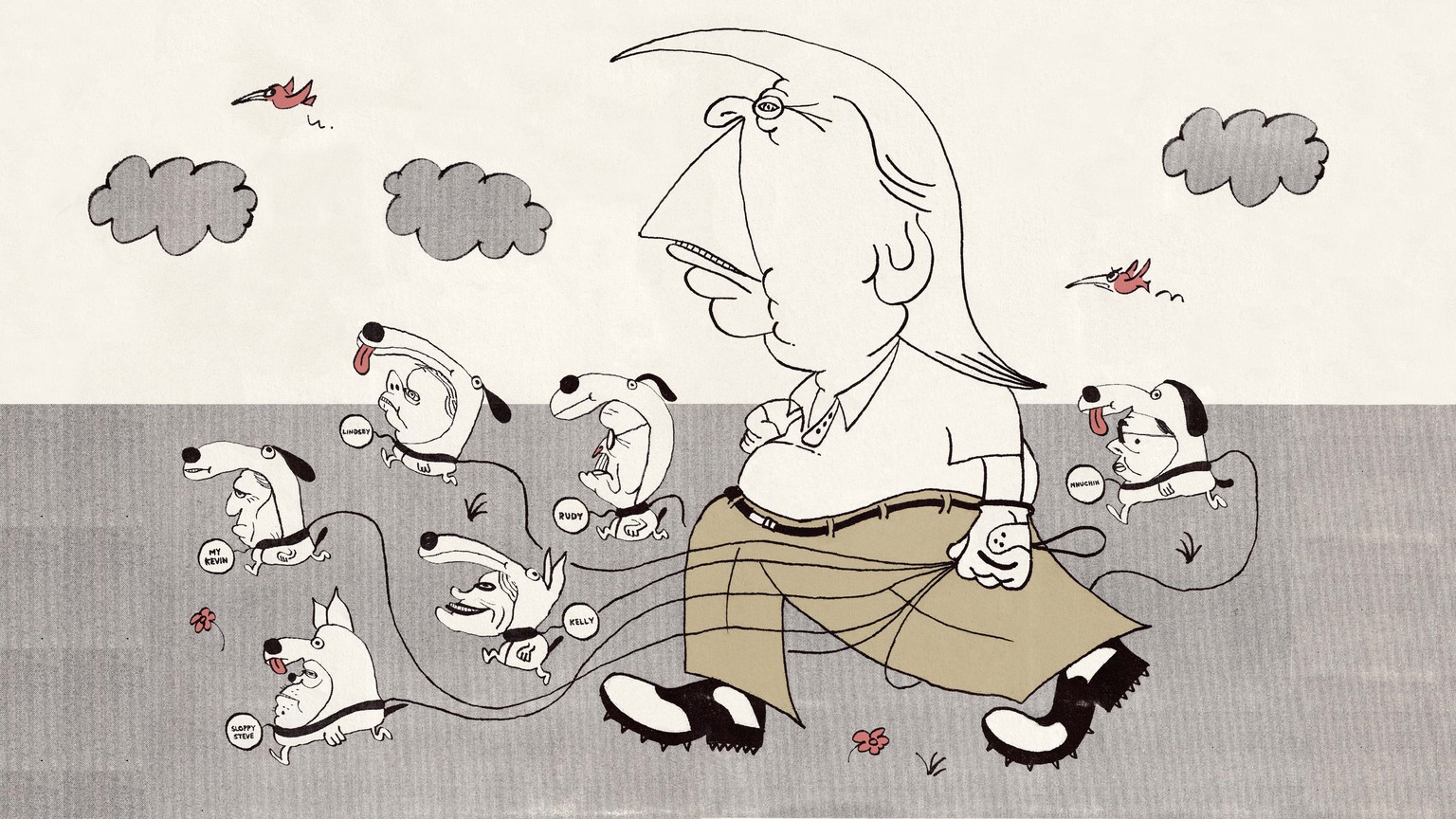

But the guests who stood out for me most were Republican House Leader Kevin McCarthy and the busybody senator from South Carolina, Lindsey Graham. I would sometimes see them around the lobby or steakhouse or function rooms, skipping from table to table and getting thanked for all the wonderful things they were doing to help our president. They had long been among the most supplicant super-careerists ever to play in a city known for the breed, and proved themselves to be essential lapdogs in Trump’s kennel.

Graham remains perhaps Trump’s closest collaborator in the Senate, a frequent golf partner and nuanced handler of the presidential ego. This week, he was subpoenaed as part of an investigation into election meddling. He might now have to testify about what exactly he was trying to do when he called Georgia’s secretary of state wondering whether he really needed to count all those mail-in votes.

I will admit I never loved the Trump story. This sometimes surprises people. I have been covering Washington for many years; I’ve been accused of being a “keen observer” of the capital. Surely, I must have been thrilled to have such a ridiculous piece of work at the center of it all, right?

Trump said and did obviously awful and dangerous things—racist and cruel and achingly dumb and downright evil things. But on top of that, he is a uniquely tiresome individual, easily the sorest loser, the most prodigious liar, and the most interminable victim ever to occupy the White House. He is, quite possibly, the biggest crybaby ever to toddle across history’s stage, from his inaugural-crowd hemorrhage on day one right down to his bitter, ketchup-flinging end.

Better objects of our scrutiny—and far more compelling to me—are the slavishly devoted Republicans whom Trump drew to his side. It’s been said before, but can never be emphasized enough: Without the complicity of the Republican Party, Donald Trump would be just a glorified geriatric Fox-watching golfer. I’ve interviewed scores of these collaborators, trying to understand why they did what they did and how they could live with it. These were the McCarthys and the Grahams and all the other busy parasitic suck-ups who made the Trump era work for them, who humored and indulged him all the way down to the last, exhausted strains of American democracy.

The GOP’s shame, ongoing, is underscored by the handful of brave Republicans willing to speak the truth about Trump in public, before the January 6 committee and on the panel itself. The question now is whether they have any hope of wresting some admirable remnant of their party back from Trump’s abyss before he wins the Republican nomination for president in 2024 or, yes, winds up back in the White House.

Nearly a decade ago I wrote a book about Washington at its (seemingly) grossest and most decadent. This Town, the book was called, and it portrayed the pre-Trump capital as a feudal village of operatives, former officeholders, minor celebrity journalists, and bipartisan coat holders. Democrats and Republicans kept coming to Washington, vowing change, only to get co-opted, get richer, and never leave.

People now toss around phrases like fundamental threat to democracy and civil war, and they don’t necessarily sound overheated. Deference to power in service to ambition has always been a Washington hallmark, but Trump has made the price of that submission so much higher.

Consider again the doormat duo—McCarthy and Graham. I’ve known both men for years, at least in the weird sense that political reporters and pols “know” each other. They are a classically Washington type: fun to be around, starstruck, and desperate to keep their jobs or get better ones—to maximize their place in the all-important mix. On various occasions I have asked them, in so many words, how they could sidle up to Trump like they have. The answer, basically, is that they did it because it was the savviest course; because it was best for them. If Trump had one well-developed intuition, it was his ability to sniff out weakness in people . . . . People like McCarthy and Graham benefited a great deal from making it work with Trump, or “managing the relationship,” as they say.

McCarthy knew that alienating Trump would blow up any chance he had of becoming speaker, which had become the singular objective of his “public service,” such as it was. . . . . But “managing the relationship” was often a daily struggle, McCarthy conceded, when I interviewed him for The New York Times in his Bakersfield, California, district in April 2021. “He goes up and down with his anger,” McCarthy said of Trump. “He’s mad at everybody one day. He’s mad at me one day … This is the tightest tightrope anyone has to walk.”

Once, early in 2019, I asked Graham a version of the question that so many of his judgy old Washington friends had been asking him. How could he swing from being one of Trump’s most merciless critics in 2016 to such a sycophant thereafter? I didn’t use those exact words, but Graham got the idea. “Well, okay, from my point of view, if you know anything about me, it’d be odd not to do this,” he told me. “‘This,’” Graham specified, “is to try to be relevant.” Relevance: It casts one hell of a spell.

There was always a breathless, racing quality to both men’s voices when they talked about the thrill ride of being one of Trump’s “guys.”

What would you do to stay relevant? That’s always been a definitional question for D.C.’s prime movers, especially the super-thirsty likes of McCarthy and Graham. If they’d never stooped this low before, maybe it’s just because no one ever asked them to.

How do you sleep at night? Trump’s protectors were always being tormented by this nuisance question. What will future historians think about how you’ve conducted yourself? was another. Do you ever think about your … you know … legacy?

Early on, when wary Republicans were still publicly dreading where the Trump experiment might lead, you’d hear flashes of concern over how it—or they—might be adjudicated by those ever-hovering future historians. As his own presidential campaign was ending in 2016, Marco Rubio predicted that there would one day be a “reckoning” inside the GOP. . . . . (Update: Rubio cleaned up his act, became a stalwart Trump patron, and we’re still waiting on that reckoning.)

“My attitude about my legacy is: Fuck it,” Rudy Giuliani told New York magazine’s Olivia Nuzzi in 2019 (his fly was unzipped at the time and he was drunk on Bloody Marys, per Nuzzi). Other versions were a bit more erudite. “Everyone dies,” Attorney General William Barr rhapsodized to CBS’s Jan Crawford in 2019. “I don’t believe in the Homeric idea that immortality comes by, you know, having odes sung about you over the centuries.”

I met with McCarthy in the spring of 2021 in a Bakersfield dessert joint . . . I tossed the pesky “legacy” question his way. . . . McCarthy kept his head down and pulled up a photo of the pope. . . . . “Here’s another of me with Trump on Air Force One,” McCarthy said. Then: “What did you ask me again?”

I repeated the question, suggesting that there might be far-reaching ramifications for his continued propping-up of Trump. McCarthy eventually looked up. “Oh, the Jeff Flake thing?” he said. No one’s putting up any statues to Flake at the Capitol, he pointed out

The response is worth unpacking, if only to underscore how dismissive McCarthy was of any suggestion that his conduct could bear historic weight beyond the day-to-day expediencies of keeping Trump’s favor. Flake and Sanford were both principled conservatives whose convictions were tested and affirmed over long careers. They freely condemned Trump throughout his rise, which led to inevitable abuse from the White House, pariah status within their party, and cancellation by “the base.” . . . . Republican colleagues would often praise Flake and Sanford for their courage and principles—but only privately.

“My legacy doesn’t matter,” Trump told his longtime aide Hope Hicks a few days after the 2020 election, according to an account in Peril, by Bob Woodward and Robert Costa. “If I lose, that will be my legacy.” This became the essential ethos of Republican nihilism. By lashing themselves so tightly to Trump, Republicans could act as if the president’s impunity and shamelessness extended to them. His strut of cavalier disregard became their own.

“Don’t care,” I overheard Graham say in early 2020 to a reporter on the Capitol subway platform who asked him whether his reputation had suffered because of his association with Trump. . . . “I don’t care if they have to stay in these facilities for 400 days,” Graham said on Fox News, about the hundreds of migrant children who had been separated from their parents and locked in cages.

No Republican spoke with more contempt for Trump during the 2016 primaries than Graham did. He called him a “complete idiot,” and “unfit for office,” among other things. But then Trump became president and deemed Graham fit to play golf with him. Suddenly Graham was getting called a “presidential confidant.”

The arrangement also proved “helpful” to Graham’s goal of continuing to represent deep-red South Carolina in the U.S. Senate. It got him into the clubhouse. It kept him fed and employed and on TV.

But Graham’s dash from McCain to McCain’s arch nemesis made him a kind of alpha lapdog. Old friends kept asking, “What happened to Lindsey?” . . . . Any ambivalence Graham had over Trump’s conduct—for example, trashing his best friend [John McCain] to the grave and beyond—was buried by the fairy dust of relevance.

McCain was never shy about voicing his low opinion of Trump, but what was really eating at him then was how readily so many of his Republican colleagues continued to abase themselves before [Trump]

the president. “It comes down to self-respect,” McCain kept saying. He also noted that a big reason Trump remained so popular with GOP voters was because most of their putative “leaders” were too afraid to defy him. “Republicans who could shape opinion just keep sucking up to the guy,” he told me.Watching the procession of GOP genuflectors, I was reminded of Susan Glasser’s 2019 profile of Secretary of State Mike Pompeo in The New Yorker, in which she quoted a former American ambassador describing Pompeo as “a heat-seeking missile for Trump’s ass.” This image stuck with me (unfortunately) and also remained a pertinent descriptor for much of the Republican Party long after said ass had been re-homed to Florida.

Like Vladimir Putin, Trump will take what people let him take. He will do what he can get away with. The courage and character of Ukraine stands in perverse contrast to America’s cowering Republican Party, whose resistance might as well have been led by the Uvalde police.

Liz Cheney, who spent years studying and working in countries with autocratic regimes in Eastern Europe and the Middle East, has made it clear that she believes the primary existential threat to America today resides within her own political party.

No comments:

Post a Comment