Selecting candidates for general elections is about picking a candidate that can both win and not wreak havoc on down ticket candidates. A long and well reasoned and researched column in the New York Times makes the case that Elizabeth Warren as the Democrat standard bearer could (i) result in Trump's re-election, and (ii) significant loses by Democrats in the House and Senate. The same reasoning applies to Bernie Sanders and, to me, makes it clear that neither Warren or Sanders should be the nominee. Their respective supporters, who the article points out tend to be the whitest and most affluent, simply are out of touch with what sells in Middle America, including among many more traditional and moderate Democrats. This is especially true in the half dozen swing states in the Mid-West that will likely decide who wins the Electoral College contest. Running up huge vote leads in say California or New York means nothing in the Electoral College math calculation. Here are lengthy column highlights which thinking Democrats need to read in full:

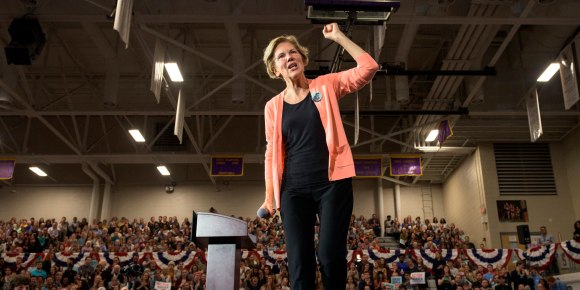

Under pressure, Elizabeth Warren has retreated from the idea of immediate implementation of Medicare for All, but she remains committed to the progressive core of her candidacy.As she put it in a speech to Iowa Democrats on Nov. 1:

If we’re going to meet the challenges of our time, we need big ideas. Big ideas to inspire people and get them out to caucus and get them out to vote. Big ideas to be the lifeblood of our party and show the world who and what Democrats will fight for.

In rhetoric that drew enthusiastic applause from her supporters at the Liberty and Justice Dinner in Des Moines, Warren declared that the nation is at “a time of crisis, and media pundits, Washington insiders, even some people in our own party don’t want to admit it. They think that running some vague campaign that nibbles around the edges is somehow safe.”

Democrats will win, she continued, “when we offer solutions big enough to touch the problems that are in people’s lives. Fear and complacency does not win elections; hope and courage wins elections.”

There is evidence, however, that Warren’s strategy could generate a backlash leading to the re-election of Donald Trump.

Andrew Hall and Daniel Thompson, political scientists at Stanford, examined “the link between the ideology of congressional candidates and the turnout of their parties’ bases in US House races, 2006—2014” in their 2018 paper “Who Punishes Extremist Nominees? Candidate Ideology and Turning Out the Base in US Elections.”

In contrast to moderate candidates, Hall and Thompson found: Extremist candidates do worse, because, contrary to rhetoric, they fail to galvanize their own base and instead encourage the opposing party’s base to turn out more, on average.

In other words, polarizing candidates diminish turnout in their own party while boosting turnout among opposing partisans.

Alan Abramowitz, a political scientist at Emory, analyzed the pattern of Democratic victories in 2018 House races and found that “those who supported Medicare for All performed worse than those who did not, even when controlling for other factors.”

The analyses by Hall, Thompson and Abramowitz do not preclude the possibility that Warren could beat Trump in 2020. Whoever the Democratic nominee is will be able to capitalize on widespread hostility to Trump, a motivated Democratic electorate and the party’s continuing gains in formerly Republican suburbs across the nation.

An underlying premise of the campaigns of both Warren and Bernie Sanders is that taking radically progressive stands will motivate, enlarge and turn out the Democratic base, including minorities, the young and the poor; and that such positions are necessary to restore Democratic support among those who voted for third party candidates in 2016.

As much as the Warren program has mobilized many Democratic primary voters, polls show that significant numbers of swing voters — wavering Republicans repelled by President Trump and moderate to conservative Democrats — do not share Warren’s appetite for major structural change, preferring incremental change and the repair of existing programs, like Obamacare.

Strategically, if Warren wins the Democratic nomination, the election would become not only a referendum on Trump — favorable terrain for Democrats — but also a referendum on Warren’s program, a far less certain proposition.

“Many of Senator Warren’s proposals are indeed radical and could have unintended consequences,” Jeffrey Frankel, an economist at Harvard’s Kennedy School and a member of the Council of Economic Advisers during the Clinton administration, wrote by email. He added: “I fear that by far the worst of the unintended consequences of making these proposals during the campaign is to get Donald Trump re-elected.”

Larry Summers is a former secretary of the Treasury, director of the national economic council and president of Harvard. The Warren program, Summers wrote by email, “dwarfs the errors, economic and political, of George McGovern.”

Last week, in an effort to mute criticism that her agenda would be not only difficult to enact in toto but also highly disruptive if it became law, Warren announced a significant modification of her version of Medicare for All. Instead of trying to immediately pass a complete government takeover of health care that would eliminate private insurance plans, she proposed “a true Medicare for All option,” or what has generally been described as a public option — and that has strong support among voters of all stripes.

Warren’s new stance appears to be an acknowledgment of the fact that her proposal to replace all health private coverage with Medicare for All does not carry majority support even among Democratic primary voters, a liberal constituency, much less the general electorate.

While liberal economists have mixed views of Warren’s agenda, a number of political observers warn that candidates for the House and Senate would face a steeper climb to victory with Warren at the top of the ticket.

“It would be tough to run under Elizabeth Warren,” David Wasserman, who studies House races for the Cook Report, said in an interview. “As of now, she runs the weakest against Trump in battleground areas and her proposals are not broadly popular.”

The worst case scenario, Wasserman argued, “would be to have Elizabeth Warren at the top of ticket with a plausible chance to win.” He argued that swing voters worried about a Warren presidency would vote in support of a Republican Congress to act as a check on her.

“Anyone at the top of the ticket who repels these Republicans will make it more difficult to win the key House and Senate seats Democrats have targeted,” Trippi said.

Whit Ayres, president of North Star Opinion Research, was outspoken: “Elizabeth Warren is God’s gift to Donald Trump and Republican candidates.”

“Well-educated suburban voters, especially women,” Ayres continued, “are uncomfortable with President Trump,” but, he added, they are not going to vote for a candidate who wants to take away their private health insurance, decriminalize the border, increase government spending by 50 percent, and ban fracking, especially in Pennsylvania, Ohio and Colorado.

Wariness toward the kind of disruptive structural change Warren is calling for can be seen among Democratic voters in six battleground states — Michigan, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, Arizona and Florida — as a New York Times/Siena College survey conducted Oct. 13-26 demonstrated.

By 62 to 33, these Democrats said they would prefer a candidates who promises “to find common ground with Republicans” to one who promises “to fight for a bold progressive agenda;” by 55 to 36 a candidate who is more “moderate than most Democrats” to one who is “more liberal than most Democrats;” and by 49 to 45 a candidate who promises “to bring politics in Washington back to normal” to a candidate who promises “to bring fundamental, systematic change to American society.”

The same Times/Siena College survey identified 596 undecided or “persuadable” voters in these six states . . . They are fairly clear about what they would like from a Democrat. They prefer, by 82 percent to 11 percent, one who promises to find common ground over one who promises to fight for a progressive agenda; and they prefer a moderate over a liberal, 75 percent to 19 percent.

Patterson’s analysis points to the larger question that looms constantly over the nomination fight: Is the progressive wing of the Democratic primary electorate, and its demand that the nominee take stands on health care, energy and immigration well to the left of the electorate at large, the main obstacle to Democratic victory in 2020?

No comments:

Post a Comment