Early last month, the White House convened a meeting of right-wing influencers for a livestreamed discussion of antifa and the danger they claim it poses. Over the course of the roundtable, President Donald Trump suggested that protests against him had been organized by mysterious funders, who he hinted could soon be in “deep trouble.” He complained about television networks that were biased against him but praised CBS, whose parent company had recently been purchased by a Trump-friendly billionaire. . . . “We took the freedom of speech away,” the president said. . . . . Trump’s comment did reflect a deeper truth about his administration’s effort to force an abrupt contraction of American civic space.

During the first 10 months of Trump’s second term in office, the federal government has cracked down on political expression—often understood as the most protected category of speech—with a persistence and viciousness reminiscent of some of the darkest periods of U.S. history. The administration has pushed for the prosecution of the president’s political opponents, fired government employees for taking positions perceived as less than entirely loyal to Trump, and barred certain law firms from working with the government because they displeased the president. It blocked AP reporters from the White House press pool because the wire service refused to refer to the Gulf of Mexico as the “Gulf of America.” It has investigated media companies and threatened to withhold merger approvals unless networks get rid of DEI policies; slashed billions of dollars in grants that it characterized as deriving from “immoral” and “illegal” DEI practices; and withheld funding for high-profile universities such as Harvard and Columbia with the goal of forcing their capitulation to the administration’s political agenda.

Following the murder of the right-wing influencer Charlie Kirk, in September, the administration called for the repression of left-leaning political views and revoked the visas of six foreigners who had criticized Kirk online. Months earlier, it snatched up and attempted to deport foreign students studying at U.S. universities who had criticized Israel, deriding them as “pro-Hamas.”

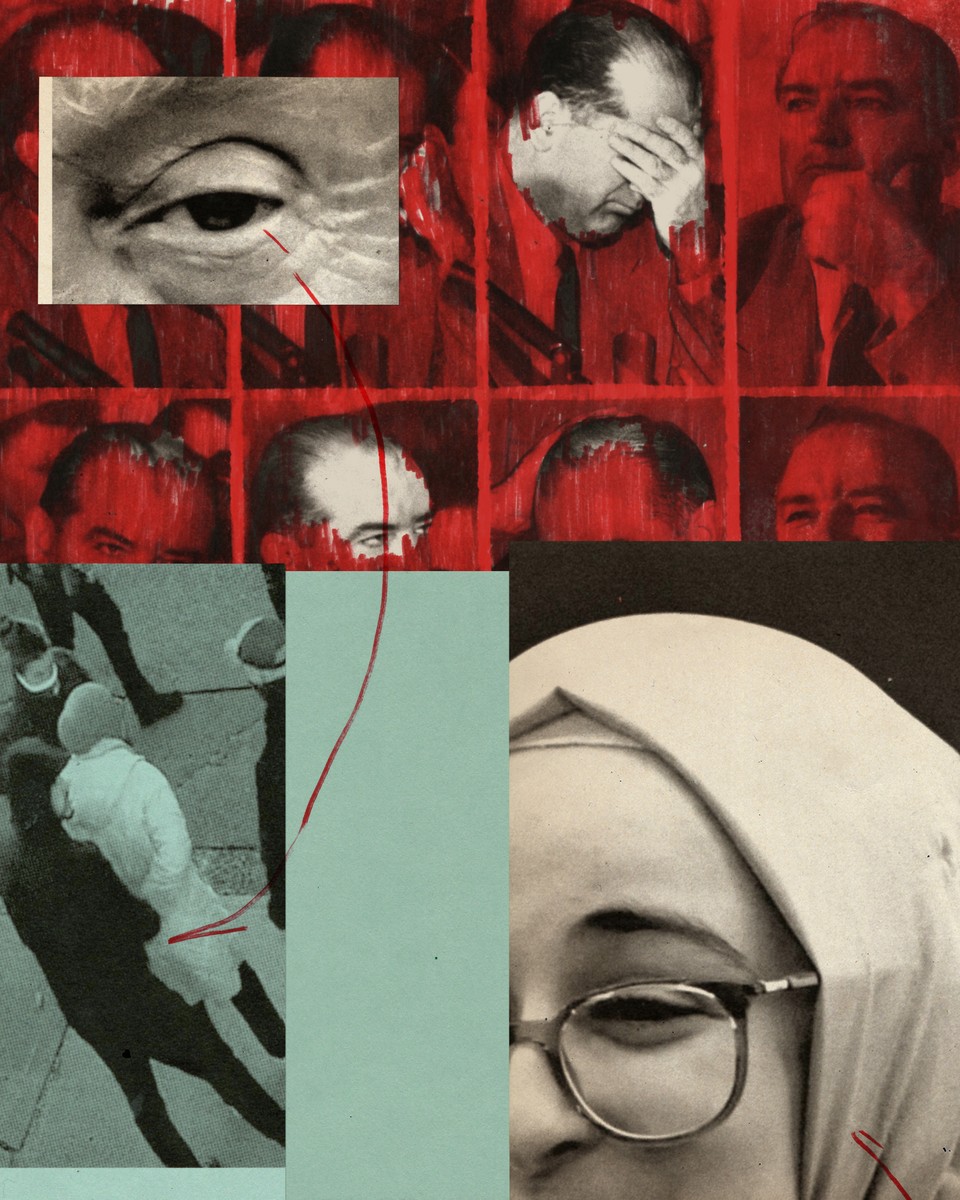

These attacks are dizzying in their variety. But they are best understood in the aggregate, as facets of a single campaign to destroy the American public sphere and rebuild it scrubbed of political opposition. In that respect, Trump’s crusade of repression bears a resemblance to the ongoing silencing of dissent in other backsliding democracies around the world, such as Turkey, Hungary, and India. After federal immigration agents grabbed Rumeysa Özturk, a Turkish Ph.D. student at Tufts University, off a Boston-area street—apparently in retaliation for her co-authorship of an op-ed criticizing Israel—a group of Massachusetts members of Congress compared the abduction to the 2020 arrest of a dissident by secret police in Belarus. Cases such as Özturk’s, the representatives wrote in The New York Times, bring the country “closer to the authoritarianism we once believed could never take root on American soil.”

Yet the Trump administration’s effort to crush dissent is not without American precedent. On a single day in 1920, the Justice Department rounded up thousands of people for deportation because of their supposed Communist sympathies, though many had little or nothing to do with the Communist Party. In Boston, not far from where Özturk was arrested, some “aliens” were handcuffed and chained together while authorities marched them down the street in front of photographers. Those raids were the peak of what is now known as the first Red Scare—a period of paranoia about Communism and anarchism that began around the time of America’s entry into World War I. Three decades later, the country plunged into the second Red Scare, a rampage against supposed Communist plots often remembered by the name of its most famous proponent, Republican Senator Joe McCarthy. Accused “reds” were hauled in front of Congress, lost their jobs, and retreated from public life.

Our new Red Scare, like the first, is obsessed with immigration and the potential of left-wing political violence—then, anarchists and Communists; today, the imagined, shadowy antifa. Like the second, it is coupled with unease about changing norms regarding gender and sexuality. The anti-Communist fervor of the late 1940s and ’50s generated suspicion of women in positions of authority within government and drove thousands of gay and lesbian government employees out of the federal workforce, in what the historian David K. Johnson termed the “Lavender Scare.”

Now the Trump administration’s anxiety about the erosion of rigid gender roles manifests in its disdain for feminism—early in the administration, agencies removed material on women’s achievements from their websites—and in its aggressive hostility toward transgender people, whom the government has pushed out of the armed forces and erased from National Park Service websites. . . . . “The word ‘woke’ now performs the job that ‘communism’ did in the 1950s,” Silver told me over email.

In a country that prides itself on independence and freethinking, key pillars of civil society—universities, law firms, businesses—have proved quiescent in the face of a campaign to squelch dissent. The political scientist Steven Levitsky, a prominent scholar of democratic decline, graded the early response of civil society to Trump’s onslaught as a “D-minus.” Yet as methods of repression have evolved over the past 70 years, so, too, have methods of resistance. . . . . American civil society is in some ways weaker than many had hoped, but it is also stronger than it once was.

In June 1917, in a precursor to the Trump administration’s furor over student protests at Columbia University, three students were prosecuted for printing anti-draft pamphlets. (My great-great-uncle was among them.) Then, as now, government harassment was a warning to others not to make too much noise. Similarly, in the second Red Scare, after a group of prominent screenwriters, producers, and directors—the “Hollywood Ten”—were questioned about suspected Communist sympathies by the House Un-American Activities Committee, the movie industry began quietly paring back film scripts to avoid anything too left-wing.

Contemporary First Amendment law refers to this dynamic as a “chilling effect,” and there is a great deal of it in the United States right now.. . . . In Texas, where several professors and university administrators have been pushed out or otherwise punished following MAGA outrage, some academics say they are anxious about the potential career repercussions of teaching subjects as previously anodyne as the women’s suffrage movement and gender-bending comedies by Shakespeare. In Tennessee, a retired police officer spent more than a month in jail after sharing a Facebook meme in response to Charlie Kirk’s death. Large law firms are wary of affiliating themselves with politicized causes, lest they be targeted by Trump’s wrath . . .

The historians, lawyers, and scholars I spoke with were in marked agreement that the current moment is not just comparable to but even more damaging than previous Red Scares. Within higher education, today’s crackdown is “worse than McCarthyism—much worse,” Ellen Schrecker, a historian and the author of No Ivory Tower: McCarthyism and the Universities, told me. Then, she explained, individual academics were scrutinized and fired for Communist ties. But today, the country is experiencing a “frontal attack on everything that has to do with universities and colleges,” Schrecker said.

This assault on higher education is best understood as a means of destroying a locus of political opposition. With growing political polarization along educational lines, college-educated voters have become more likely to vote for the Democratic Party. Trump’s solution is an attempted dismantling of the institutions that helped produce these voters in the first place—and a symbolic attack on institutions of knowledge and expertise that are inherently at odds with Trump’s model of governance by know-nothingism.

This overtly partisan cast distinguishes Trump’s campaign to crush dissent from America’s fits of anti-Communist paranoia in the early and mid-20th century, which were more bipartisan affairs. . . . The government’s legal tactics have changed since the first and second Red Scares, in large part because the protections offered by the contemporary First Amendment are far more robust. Today’s law of free speech itself evolved “as a reaction to the problems of the McCarthy Era,” the First Amendment scholar Genevieve Lakier recently wrote. For this reason, Trump would have far more difficulty, say, prosecuting Columbia students simply for handing out pamphlets.

The flip side is that political speech unambiguously by Americans, about America, receives strong legal protections. It’s here that Trump has come to rely on more indirect methods of pressure—chiefly involving the withholding of money. Universities are far more vulnerable to presidential pressure today than they were during the second Red Scare, thanks to the massive amount of federal funding that the government has poured into higher education over the past 70 years. Trump is now dangling the potential loss of that same funding over schools to get them to bend to his will, and in many cases it is working in his favor.

The Federal Communications Commission, meanwhile, has leveraged a consolidated media landscape by threatening to withhold merger approvals unless companies pledge fealty to Trump. FCC Chair Brendan Carr approved an $8 billion merger between the media giants Skydance and Paramount, which owns CBS, only after Paramount handed Trump $16 million to settle a baseless lawsuit and Skydance agreed to install a Trump-friendly ombudsman at the network.

When I spoke with Schrecker about her study of the second Red Scare, she pointed to Kimmel’s victory as an indication of the difference between the McCarthy era and today. During McCarthyism, “there was essentially no opposition,” she told me. “People either supported the purges, or else they were too afraid.” One representative anecdote in No Ivory Tower describes a graduate student at the University of Chicago who, during the ’50s, was unable to persuade frightened colleagues to sign a petition—not about any politically sensitive topic but for the university to install a vending machine in their laboratory. In contrast, after Disney pulled Kimmel from the air, petitions and calls for boycotts blossomed. The ACLU launched a campaign to “defend free speech,” and hundreds of actors and artists signed on.

Reading No Ivory Tower, I was struck by how little organizations such as the ACLU and the AAUP, the professors’ association, did to protect academics from McCarthy’s censorship. Today, both organizations have been aggressive in pushing back. The ACLU recently announced that it has filed more than 100 lawsuits against the second Trump administration; in addition to its lawsuit over attempted deportations of foreign students, the AAUP has filed suits against a variety of the administration’s efforts to target higher education. Many civic institutions have buckled under pressure, but the ruckus made by the others is far louder than any of the muted pushback against McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Committee.

The institutions that initially caved have, paradoxically, tended to be bigger and wealthier—Paramount, Columbia University, prominent law firms. Such organizations “are in many instances actually more vulnerable, because they have more pain points—federal grants, licenses, merger approvals—that the Administration can use to exert leverage,” Fabio Bertoni, The New Yorker’s general counsel, writes in a reflection on why elite law firms gave in to Trump.

But it is also a story about another set of crucial changes in American life since this period: the maturation of litigating organizations such as the ACLU, along with legal and cultural shifts that have made Americans more comfortable with the idea of taking the government to court. . . . . “Civil liberties organizations have vastly more capacity” than they did in the ’50s, Epp explained over email, and that growth “helps to explain why the litigation against the Trump initiatives is so much more widespread than in the 1950s and early 1960s.” . . . . Litigation against contemporary attacks on democracy follows in that tradition. “Some of the institutions that have caved are simply ones that had never been tested with this kind of challenge,” Ifill said. “But for us, that’s kind of baked into the pie.”

No comments:

Post a Comment