When I review divided appellate-court decisions, I almost always read the dissenting opinions first. The habit formed back when I was a young law student and lawyer—and Federalist Society member—in the late 1980s, when I would pore (and, I confess, usually coo) over Justice Antonin Scalia’s latest dissents.

I came to adopt the practice not just for newsworthy rulings that I disagreed with, but for decisions I agreed with, including even obscure cases in the areas of business law I practiced. Dissents are generally shorter, and almost always more fun to read, than majority opinions; judges usually feel freer to express themselves when writing separately. But dissents are also intellectually useful: If there’s a weakness in the majority’s argument, an able judge will expose it, sometimes brutally, and she may make you change your mind, or at least be less dismissive of her position, even when you disagree. . . . . You can learn a lot from dissents.

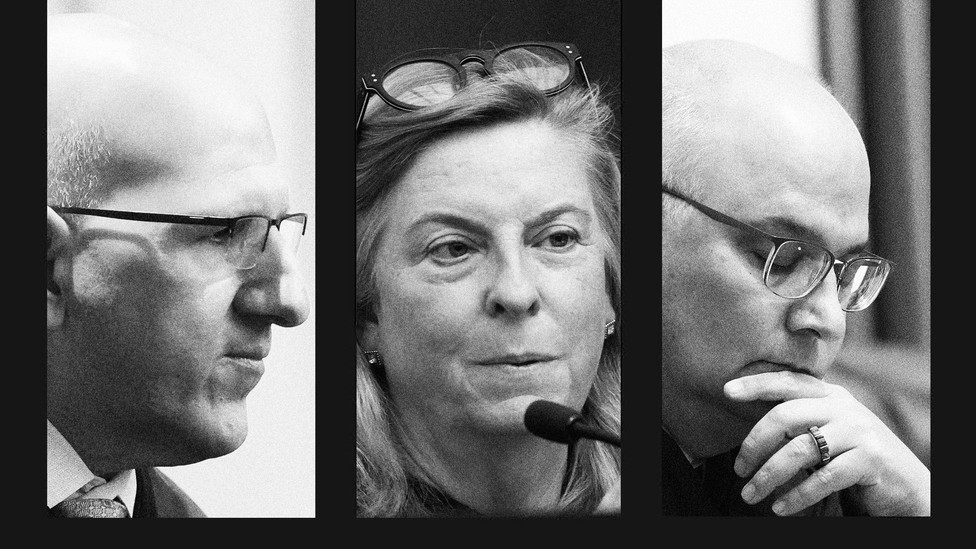

Last night, I reviewed the three separate dissents in Anderson v. Griswold, the landmark 4–3 Colorado Supreme Court case holding that Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment prohibits Donald Trump from ever serving again as president of the United States. I had been skeptical of the argument, but not for any concrete legal reason. To the contrary, I believed the masterful article written by the law professors (and Federalist Society members) William Baude and Michael Stokes Paulsen had put the argument into play. . . . the Fourteenth Amendment clearly commands, in plain language, that Trump never hold federal office again.

The argument seemed somehow too good to be true. . . . But last night changed my mind. Not because of anything the Colorado Supreme Court majority said. The three dissents were what convinced me the majority was right.

The dissents were gobsmacking—for their weakness. They did not want for legal craftsmanship, but they did lack any semblance of a convincing argument.

For starters, none of the dissents challenged the district court’s factual finding that Trump had engaged in an insurrection. None of the dissents seriously questioned that, under Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment, Trump is barred from office if he did so. Nor could they. The constitutional language is plain.

Nor did the dissents challenge the evidence—adduced during a five-day bench trial, and which, three years ago, we saw for ourselves in real time—that Trump had engaged in an insurrection by any reasonable understanding of the term. And the dissenters didn’t even bother with the district court’s bizarre position that even though Trump is an insurrectionist, Section 3 doesn’t apply to him because the person holding what the Constitution itself calls the “Office of the President” is, somehow, not an “officer of the United States.”

Instead, the three dissenters mostly confined themselves to saying that state law doesn’t provide the plaintiffs with a remedy. But that won’t help Trump. This case seems headed for the Supreme Court of the United States, which has no authority to make definitive pronouncements about state law. In Colorado, the Supreme Court of Colorado has the last word on that. And it now has spoken.

Yet even the dissenters’ contentions about state law made little sense.

Every qualification necessarily establishes a disqualification. If the Constitution says, as it does, that you have to be 35 years of age to serve as president, you’re out of luck—disqualified—if you’re 34 and a half. By the same token, if you’ve engaged in an insurrection against that Constitution in violation of your oath to it, you’ve failed to meet the ironclad (and rather undemanding) requirement that you not have done that.

Boatright’s suggestion that the insurrection issue presents something too complex for Colorado’s election-dispute-resolution procedures is equally unconvincing. Reviewing the tabulation of statewide votes can be complicated . . . . It’s hard to imagine that assessing the undisputed record of Trump’s miscreance presents any more complexity than that.

And no stronger is Justice Carlos Samour’s suggestion that Trump was somehow deprived of due process by the proceedings in the district court. This was a full-blown, five-day trial, with sworn witnesses and lots of documentary exhibits, all admitted under the traditional rules of evidence before a judicial officer, who then made extensive written findings of fact under a stringent standard of proof. Every day in this country, people go to prison—for years—with a lot less process than Trump got here.

The closest the dissents come to presenting a federal-law issue that ought to give someone pause comes in Samour’s argument that Section 3 is not self-executing—that it can’t be enforced unless Congress passes a law detailing how it can be enforced. The majority opinion, though, along with Paulsen and Baude and Luttig and Tribe, have disposed of that argument many times over. All you need to do is to look, as any good Scalia-like textualist would, to the words and structure of the Fourteenth Amendment.

True, Section 5 of the amendment gives Congress the power to enact enforcement legislation. But nothing in the amendment suggests that such legislation is required . . . . To hold otherwise would mean that Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment—which contains the more familiar prohibitions against state deprivations of equal protection and due process—would likewise have been born toothless. Which would mean that, if every federal civil-rights statute were repealed tomorrow, states could immediately start racially resegregating their schools. That’s not the law, and thankfully so.

So the dissents showed one thing clearly: The Colorado majority was right. I dare not predict what will happen next. But if Trump’s lawyers or any members of the United States Supreme Court want to overturn the decision, they’d better come up with something much, much stronger.

Thoughts on Life, Love, Politics, Hypocrisy and Coming Out in Mid-Life

Tuesday, December 26, 2023

The Colorado Supreme Court Got It Right

If the U.S. Supreme Court were not in the grips of a reactionary majority there, in my view, should be little doubt that the ruling of the Colorado Supreme Court barring Donald Trump from that state's ballot would be affirmed and the stage would be set to rid the Trump menace from the nation. The Court's majority that pretends to be originalists would have no way to circumvent the very clear express language of the 14th Amendment that bars insurrectionists from office. As more and more evidence of Trump's misdeeds continues to be brought forward and as everyone outside of the MAGA understands and saw with their own eyes, Trump intentionally unleashed a rabid and violent mob on the U.S. Capitol with one purpose: to stop the election he had lost and to illegally remain in office in violation of the U.S. Constitution and to in effect overthrow the government. If the U.S. Supreme Court fails to affirm the Colorado ruling, then that Court should lose what little legitimacy it has remaining after Dobbs and other anti-democracy rulings. A column in The Atlantic by George Conway lays out why the Colorado ruling is correct and must be affirmed. Here are highlights:

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment