Politicians - especially Republicans - bloviate about freedom and "American exceptionalism" while ignoring the continued shrinking of Americans' life expectancy versus that of other advanced nations (peer nations, if you will). Yes, America is exceptional, but in a very bad way. There are numerous factors behind this national disgrace, not the least of which America's lack of universal health care thanks to Republicans that in effect often relegates poorer Americans - many of them working class whites, not just blacks - to an all too often premature death. Add to this America's worsening gun carnage which the GOP backed loosen of gun control will only intensify, our higher roadway carnage, the epidemic of drug overdoses and the FDA's reticence in approving drugs widely used in Europe, the picture is truly ugly. Of course, things don't have to be this way if politicans had the will to focus on the problem, cease stoking racial and social division and, instead, pushed for a focus on the common good. A piece in The Atlantic looks at this disgraceful aspect of "American exceptionalism" which sadly appears to be worsening. Here are article highlights:

The true test of a civilization may be the answer to a basic question: Can it keep its children alive?

For most of recorded history, the answer everywhere was plainly no. Roughly half of all people—tens of billions of us—died before finishing puberty until about the 1700s, when breakthroughs in medicine and hygiene led to tremendous advances in longevity. In Central Europe, for example, the mortality rate for children fell from roughly 50 percent in 1750 to 0.3 percent in 2020. You will not find more unambiguous evidence of human progress.

How’s the U.S. doing on the civilization test? When graded on a curve against its peer nations, it is failing. The U.S. mortality rate is much higher, at almost every age, than that of most of Europe, Japan, and Australia. That is, compared with the citizens of these nations, American infants are less likely to turn 5, American teenagers are less likely to turn 30, and American 30-somethings are less likely to survive to retirement.

Last year, I called the U.S. the rich death trap of the modern world. The “rich” part is important to observe and hard to overstate. The typical American spends almost 50 percent more each year than the typical Brit, and a trucker in Oklahoma earns more than a doctor in Portugal.

This extra cash ought to buy us more years of living. For most countries, higher incomes translate automatically into longer lives. But not for today’s Americans. A new analysis by John Burn-Murdoch, a data journalist at the Financial Times, shows that the typical American is 100 percent more likely to die than the typical Western European at almost every age from birth until retirement.

Imagine I offered you a pill and told you that taking this mystery medication would have two effects. First, it would increase your disposable income by almost half. Second, it would double your odds of dying in the next 365 days. To be an average American is to fill a lifetime prescription of that medication and take the pill nightly.

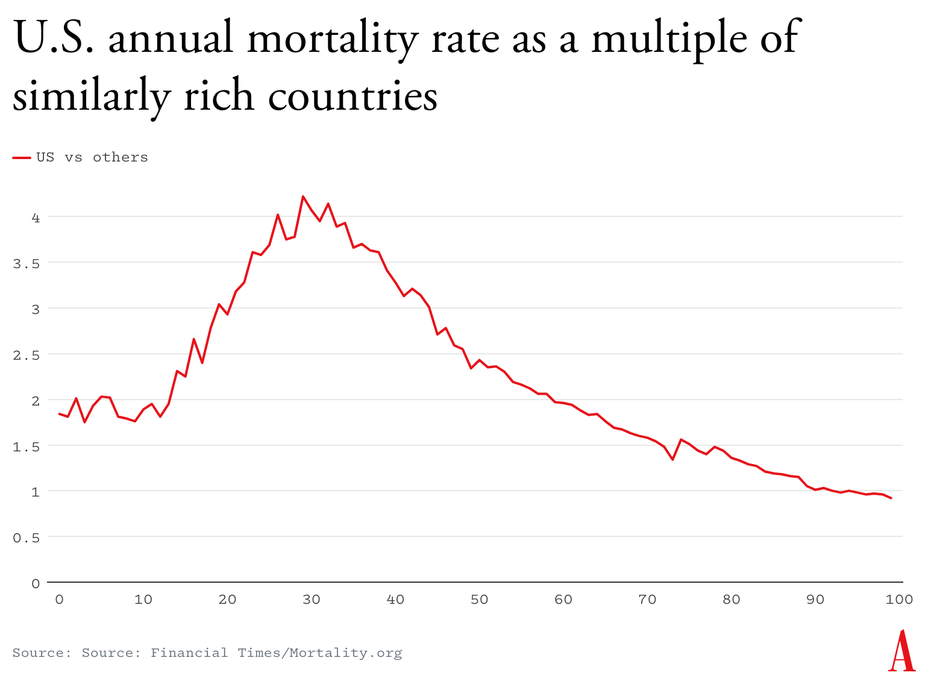

According to data collected by Burn-Murdoch, a typical American baby is about 1.8 times more likely to die in her first year than the average infant from a group of similarly rich countries: Australia, Austria, Switzerland, Germany, France, the U.K., Japan, the Netherlands, and Sweden. Let’s think of this 1.8 figure as “the U.S. death ratio”—the annual mortality rate in the U.S., as a multiple of similarly rich countries.

By the time an American turns 18, the U.S. death ratio surges to 2.8. By 29, the U.S. death ratio rockets to its peak of 4.22, meaning that the typical American is more than four times more likely to die than the average resident in our basket of high-income nations. In direct country-to-country comparisons, the ratio is even higher. The average American my age, in his mid-to-late 30s, is roughly six times more likely to die in the next year than his counterpart in Switzerland.

[T]he typical middle-aged American is roughly three times more likely to die within the year than his counterpart in Western Europe or Australia. Only in our late 80s and 90s are Americans statistically on par, or even slightly better off, than residents of other rich nations.

What is going on here? The first logical suspect might be guns. According to a recent Pew analysis of CDC data, gun deaths among U.S. children and teens have doubled in the past 10 years, reaching the highest level of gun violence against children recorded this century. . . . . People everywhere suffer from mental-health problems, rage, and fear. But Americans have more guns to channel those all-too-human emotions into a bullet fired at another person.

One could tell a similar story about drug overdoses and car deaths. In all of these cases, America suffers not from a monopoly on despair and aggression, but from an oversupply of instruments of death. We have more drug-overdose deaths than any other high-income country because we have so much more fentanyl, even per capita. Americans drive more than other countries, leading to our higher-than-average death rate from road accidents. Even on a per-miles-driven basis, our death rate is extraordinary.

Americans’ health (and access to health care) seems to be the most important factor. America’s prevalence of cardiovascular and metabolic disease is so high that it accounts for more of our early mortality than guns, drugs, and cars combined.

Disentangling America’s health issues is complicated, but I can offer three data points. First, American obesity is unusually high, which likely leads to a larger number of early and middle-aged deaths. Second, Americans are unusually sedentary. We take at least 30 percent fewer steps a day than people do in Australia, Switzerland, and Japan. Finally, U.S. access to care is unusually unequal—and our health-care outcomes are unusually tied to income. As the Northwestern University economist Hannes Schwandt found, Black teens in the poorest U.S. areas are roughly twice as likely to die before they turn 20 as teenagers in the richest counties. This outcome is logically downstream of America’s paucity of universal care and our shortage of physicians, especially in low-income areas.

[V]oters and politicians in the U.S. care so much about freedom in that old-fashioned ’Merica-lovin’ kind of way that we’re unwilling to promote public safety if those rules constrict individual choice. That’s how you get a country with infamously laissez-faire firearms laws, more guns than people, lax and poorly enforced driving laws, and a conservative movement that has repeatedly tried to block, overturn, or limit the expansion of universal health insurance on the grounds that it impedes consumer choice. Among the rich, this hyper-individualistic mindset can manifest as a smash-and-grab attitude toward life, with surprising consequences for the less fortunate.

In medicine, excessive regulation and risk aversion on the part of the FDA and Institutional Review Boards have very likely slowed the development and adoption of new lifesaving treatments. This has created what the economist Alex Tabarrok calls an “invisible graveyard” of people killed by regulators preventing access to therapies that would have saved their life.

America is caught in a lurch between oversight and overkill, sometimes promoting individual freedom, with luridly fatal consequences, and sometimes blocking policies and products, with subtly fatal consequences. That’s not straightforward, and it’s damn hard to solve. But mortality rates are the final test of civilization. Who said that test should be easy?

No comments:

Post a Comment