In the terrible winter of 1932–33, brigades of Communist Party activists went house to house in the Ukrainian countryside, looking for food. The brigades were from Moscow, Kyiv, and Kharkiv, as well as villages down the road. They dug up gardens, broke open walls, and used long rods to poke up chimneys, searching for hidden grain. They watched for smoke coming from chimneys, because that might mean a family had hidden flour and was baking bread. They led away farm animals and confiscated tomato seedlings. After they left, Ukrainian peasants, deprived of food, ate rats, frogs, and boiled grass. They gnawed on tree bark and leather. Many resorted to cannibalism to stay alive. Some 4 million died of starvation.

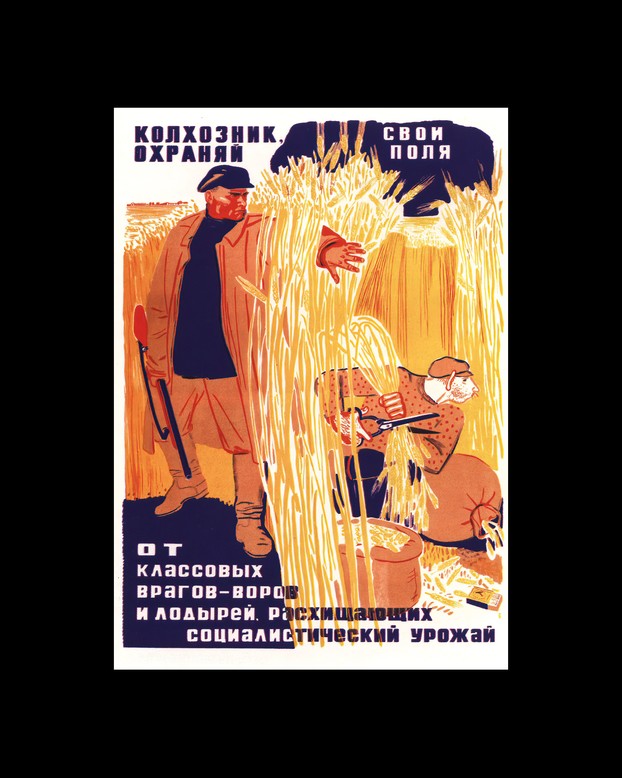

At the time, the activists felt no guilt. Soviet propaganda had repeatedly told them that supposedly wealthy peasants, whom they called kulaks, were saboteurs and enemies—rich, stubborn landowners who were preventing the Soviet proletariat from achieving the utopia that its leaders had promised. The kulaks should be swept away, crushed like parasites or flies.

Years later, the Ukrainian-born Soviet defector Viktor Kravchenko wrote about what it was like to be part of one of those brigades. . . . . He also described how political jargon and euphemisms helped camouflage the reality of what they were doing.

Lev Kopelev, another Soviet writer who as a young man had served in an activist brigade in the countryside (later he spent years in the Gulag), had very similar reflections. He too had found that clichés and ideological language helped him hide what he was doing, even from himself:

I persuaded myself, explained to myself. I mustn’t give in to debilitating pity. We were realizing historical necessity. We were performing our revolutionary duty. We were obtaining grain for the socialist fatherland. For the five-year plan.

There was no need to feel sympathy for the peasants. They did not deserve to exist. Their rural riches would soon be the property of all.

But the kulaks were not rich; they were starving. The countryside was not wealthy; it was a wasteland.

Nine decades have passed since those events took place. The Soviet Union no longer exists. The works of Kopelev, Kravchenko, and Grossman have long been available to Russian readers who want them. . . . Once, we assumed that the mere telling of these stories would make it impossible for anyone to repeat them. But although the same books are theoretically still available, few people buy them. Memorial, the most important historical society in Russia, has been forced to close. Official museums and monuments to the victims remain small and obscure. Instead of declining, the Russian state’s ability to disguise reality from its citizens and to dehumanize its enemies has grown stronger and more powerful than ever.

Nowadays, less violence is required to misinform the public: There have been no mass arrests in Putin’s Russia on the scale used in Stalin’s Russia. Perhaps there don’t need to be, because Russian state-run television, the primary source of information for most Russians, is more entertaining, more sophisticated, more stylish than programs on the crackly radios of Stalin’s era. Social media is far more addictive and absorbing than the badly printed newspapers of that era, too.

The modern Russian state has also set the bar lower. Instead of offering its citizens a vision of utopia, it wants them to be cynical and passive; whether they actually believe what the state tells them is irrelevant. Although Soviet leaders lied, they tried to make their falsehoods seem real. . . . . In Putin’s Russia, politicians and television personalities play a different game, one that we in America know from the political campaigns of Donald Trump. They lie constantly, blatantly, obviously. But if you accuse them of lying, they don’t bother to offer counterarguments. . . . . This constant stream of falsehoods produces not outrage, but apathy. Given so many explanations, how can you know whether anything is ever true? What if nothing is ever true?

[M]odern Russian propaganda has for the past decade focused on enemies. Russians are told very little about what happens in their own towns or cities. As a result, they aren’t forced, as Soviet citizens once were, to confront the gap between reality and fiction. Instead, they are told constantly about places they don’t know and have mostly never seen: America, France and Britain, Sweden and Poland—places filled with degeneracy, hypocrisy, and “Russophobia.”

If anything, the portrayal of America has been worse. U.S. citizens who rarely think about Russia would be stunned to learn how much time Russian state television devotes to the American people, American politics, even American culture wars.

Within the ever-changing drama of anger and fear that unfolds every night on the Russian evening news, Ukraine has long played a special role. In Russian propaganda, Ukraine is a fake country, one without history or legitimacy, a place that is, in the words of Putin himself, nothing more than the “southwest” of Russia, an inalienable part of Russia’s “history, culture and spiritual space.” Worse, Putin says, this fake state has been weaponized by the degenerate, dying Western powers into a hostile “anti-Russia.”

Putin invaded Ukraine in order to turn it into a colony with a puppet regime himself, because he cannot conceive of it ever being anything else. His KGB-influenced imagination does not allow for the possibility of authentic politics, grassroots movements, even public opinion. In Putin’s language, and in the language of most Russian television commentators, the Ukrainians have no agency. They can’t make choices for themselves. They can’t elect a government for themselves. They aren’t even human—they are “Nazis.” And so, like the kulaks before them, they can be eliminated with no remorse.

But while not every use of genocidal hate speech leads to genocide, all genocides have been preceded by genocidal hate speech. The modern Russian propaganda state turned out to be the ideal vehicle both for carrying out mass murder and for hiding it from the public. The gray apparatchiks, FSB operatives, and well-coiffed anchorwomen who organize and conduct the national conversation had for years been preparing their compatriots to feel no pity for Ukraine.

They succeeded. From the first days of the war, it was evident that the Russian military had planned in advance for many civilians, perhaps millions, to be killed, wounded, or displaced from their homes in Ukraine. Other assaults on cities throughout history—Dresden, Coventry, Hiroshima, Nagasaki—took place only after years of terrible conflict. By contrast, systematic bombardment of civilians in Ukraine began only days into an unprovoked invasion. In the first week of the war, Russian missiles and artillery targeted apartment blocks, hospitals, and schools. . . . . In the first three weeks of the war alone, Human Rights Watch documented cases of summary execution, rape, and the mass looting of civilian property. .

Mariupol, a mostly Russian-speaking city the size of Miami, was subjected to almost total devastation. . . . Men, women, and children died of starvation and dehydration. Those who tried to escape were fired upon. Outsiders who tried to bring in supplies were fired upon as well. The bodies of the dead, both Ukrainian civilians and Russian soldiers, lay in the street, unburied, for many days.

The dehumanization of the Ukrainians was completed in early April, when RIA Novosti, a state-run website, published an article arguing that the “de-Nazification” of Ukraine would require the “liquidation” of the Ukrainian leadership, and even the erasure of the very name of Ukraine, because to be Ukrainian was to be a Nazi: “Ukrainianism is an artificial anti-Russian construct, which does not have any civilizational content of its own, and is a subordinate element of a foreign and alien civilization.”

Few feel remorse. Published recordings of telephone calls between Russian soldiers and their families—they are using ordinary SIM cards, so it’s easy to listen to them—are full of contempt for Ukrainians. “I shot the car,” one soldier tells a woman, perhaps his wife or sister, in one of the calls. “Shoot the motherfuckers,” she responds, “as long as it’s not you. Fuck them. Fucking drug addicts and Nazis.”

All of this—the indifference to violence, the amoral nonchalance about mass murder, even the disdain for the lives of Russian soldiers—is familiar to anyone who knows Soviet history (or German history, for that matter). But Russian citizens and Russian soldiers either don’t know that history or don’t care about it.

There was no reckoning after the Ukrainian famine, or the Gulag, or the Great Terror of 1937–38, no moment when the perpetrators expressed formal, institutional regret. Now we have the result.

Thoughts on Life, Love, Politics, Hypocrisy and Coming Out in Mid-Life

Tuesday, April 26, 2022

First Comes the Dehumanization. Then the Killing.

One of the most stunning and horrifying aspects of the war in Ukraine is the deliberate targeting of civilians - apartment complexes, hospitals, schools, the list goes on and on - by the Russian military. As war crimes are being documented, the Russian story line is insanely that the Ukrainians themselves have committed the attrocities notwithstanding satellite and other documentation that clearly shows the crimes were committed while areas were under Russian control. A lemgthy piece in The Atlantic - I heard the author being interviewed yesterday - looks at the long campaign by the Russian government to dehumanize those it labels as opponents and enemies, all used to create a mindset where murder can be shrugged off or somehow justified. In Russia, this mode of operation began with the Bolsheviks as they sought to wipe out the aristocrisy and anyone who opposed their ruthless agenda and has continued ever since through Stalin and now Putin's dictatorship. A similar dehumanization process was used in Nazi Germany against the Jews and even eastern Europeans of slavic descent during WWI. Frighteningly, it is being used today in America by the Christofascists against gays - it has been their practice for over 30 years - and far right Republicans and QAnon followers against Democrats. Here are article excerpts that show the danger of lies and dehumanization:

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment