Scott Soffen has long considered himself a loyal Democrat. This time last year, the apparel company owner in this southern New Jersey suburb of Philadelphia felt confident that his party’s victories would usher in sweeping change, particularly on social justice and economic inequality.

Now?

“I wake up mad every single day,” said Soffen, 69, from his home. “It’s infighting, just constant infighting.”

In the Blue Ridge Mountains of southwestern Virginia, about 300 miles away, along a highway dotted with gas stations and antique shops, Tristen Ashley was in an empty cafe. She, too, has voted for Democrats in the past, backing Joe Biden in 2020, Hillary Clinton in 2016 and Terry McAuliffe when he ran for governor in 2013. Now?

“It’s been too extreme,” said the 38-year-old who opted not to vote in last week’s Virginia election, even though McAuliffe was back on the ballot. “I think that’s where I generally have problems voting or finding a candidate that I like, because it’s hard for me to find somebody that’s willing to work across party lines and fix things.”

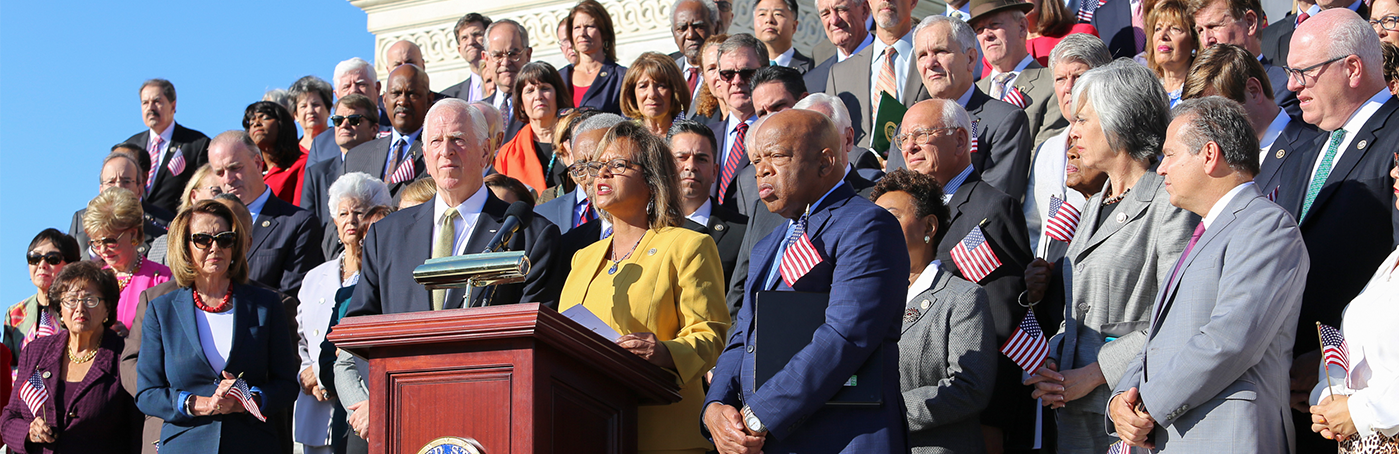

While President Biden and congressional Democrats celebrated passage Friday night of a massive infrastructure bill, danger signs remained from the party’s dismal performance in Tuesday’s elections — with Republicans sweeping statewide races in Virginia, which had been trending blue for years, and nearly toppling the incumbent Democratic governor in deeply blue New Jersey.

The results showcased Democrats’ declining support among moderate voters, particularly in suburbs, small towns and rural communities. And they helped crystallize a problem that has been lurking under the surface for some time, as described in interviews with voters and party leaders alike: the absence of a singular, unifying goal for Democrats to rally around.

While President Barack Obama provided a glue for the party in 2008 and 2012 and the animosity toward President Donald Trump brought all factions together in 2016 and 2020, the party of 2021 often functions more like a collection of smaller tribes spanning an ideological spectrum from socialism to centrism. As a result, when voters and politicians are asked to define what it means to be a Democrat, the answers are often as varied as the diverse constituencies and coalitions that make up the party.

Republicans, who have largely unified around their support for Trump, found success in last week’s elections without the former president on the ballot by reaching moderates and independents, in part by tapping into anxiety on issues including school closures and pandemic restrictions, taxes and anti-racist school curriculums they claim have gone too far.

Top Democrats now say their path forward is in enacting the infrastructure plan and passing the additional social spending measure that would fulfill a number of Biden’s promises. But some concede that it’s hard to reach many voters with complex legislation.

It remains unclear how the public will interpret the infusion of infrastructure spending into their communities, how the second social spending bill will play out — and whether those measures come to define Democrats in the eyes of voters.

In interviews over the past week with voters in breweries and cafes, grocery stores and farms in suburban New Jersey and rural Virginia, traditionally Democratic voters expressed wide-ranging views about the current state of the party. Some are alarmed that Democrats, with control of all levers of power, haven’t done more to affect their lives. Others are angry that the top issues for the White House are not the ones they care most about.

Liberals say conservatives are holding up the kinds of sweeping change the country needs. Moderates say the party has misread the electorate and risks losing the majority a year from now. And some have come to view members of their own party as a bigger enemy than Republicans.

In Nelson County, Va., a rural area that voted Democratic before turning more Republican in recent years and voted strongly for Gov.-elect Glenn Youngkin (R) last week, several voters said they were turned off by the direction of the party.

House Minority Whip James E. Clyburn (D-S.C.) has warned his party that keeping the Black community as a reliable voting bloc requires addressing policy issues such as voting rights as well as economic, social and racial disparities. He has called for the abolishment of the Senate filibuster, even a temporary one, to pass voting rights reforms.

Clyburn said the takeaway from the depressed turnout among Black voters in New Jersey and Virginia should be considered “a national problem” that could plague the party in the midterms.

Biden and other party leaders have a record of struggling to sell their programs, even after passage and even when they contain popular provisions.

Earlier in the year, for example, the Democratic-led Congress passed a $1.9 trillion stimulus bill that has largely been forgotten in the public debate.

“Every single Democrat in the country voted for a relief package that helps small business and families, gets shots in arms and addresses anxiety,” said Dan Sena, a Democratic consultant. “But we haven’t talked about that. The one thing that unifies us is what we haven’t talked about. We have this unified set of things we did at the beginning of the year that we just stopped talking about.”

Even if the party is able to unite around the latest legislation, there will remain lingering divisions over what to pursue next.

Thoughts on Life, Love, Politics, Hypocrisy and Coming Out in Mid-Life

Monday, November 08, 2021

Are Progressives Destroying the Democrat Party?

For ten months congressional Democrats put on an endless display of rancor and discord and an inability to govern. Rather than quickly pass the $1.2 trillion infrastructure bill so-called "progressives" held the bill hostage and delayed passage until last week after devastating losses in Virginia - losses that in my view might have been avoided had the infrastructure bill passed months ago - and prevented the spending in that bill prom positively impacting states, cities and localities and, most importantly working class Americans who would have seen improved employment options. It was, in my view, the height of stupidity and showcases the reality that these "progressives" - many from very liberal districts - are out of touch with the majority of Americans. Make no mistake, I am socially liberal, but I am also a pragmatist and understand that one must win over moderates and independents to win elections. Sadly, this later reality is utterly lost on individuals like AOC and Rep. Jayapal. A piece in the Washington Post looks at how this display of an inability to govern cost Democrats dearly and may continue to cost the party in the lead up to the 2022 mid-term elections. Here are highlights:

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

1 comment:

i came across this quote in an article about an upset of democrats in NY:

"...It wasn’t the high taxes in Nassau County, or the recent changes to New York’s bail laws that drove Lizette Sonsini, a former Democrat, to vote Republican this year.

Her reasons were more overarching.

'I don’t like the president, and the Democrats are spending too much money on things like infrastructure, when really we need politicians who are going to bring more money back into this country,' said Sonsini, 56, of Great Neck."

democrats would be doing themselves a much bigger favor if they could figure out exactly how republican leadership managed to convince voters that infrastructure, for some reason, IS NOT "bringing money back into this country" rather than blame progressives whose agenda of expanded medicare, free community college, child tax credits and a green energy plan is hardly what any sensible person would consider "too radical."

Post a Comment