While by most standards Joe Biden's European trip was a success and Biden and other's stated that "America is Back," meaning the country will again work with long time allies and slavish pandering to Vladimir Putin is over. But on another front, America is anything but back. Specifically, American democracy remains under steady attack by the Republican Party and its base dominated by white supremacists, Christofascists and conspiracy theory devotees. As a column in the Washington Post notes, America's image remains damaged and we are no longer seen as a premier example of democracy. Here are highlights:

One aspect of the United States’ power remains substantially diminished: its role as a beacon of democracy. Among countries surveyed, 57 percent of people said the United States is no longer the model for democracy it used to be. Young people worldwide are even more skeptical about America’s democratic institutions.

In one fundamental way, things look worse now than in prior periods of crisis. After Watergate, many were surprised that the world looked up to the United States for facing and fixing its democratic failures. It was a sign of the country’s capacity to course-correct. But imagine if after that scandal, the Republican Party, instead of condemning Nixon, had embraced him slavishly, insisted that he did absolutely nothing wrong, settled into denial and obstructionism and proposed new laws to endorse Nixon’s most egregious conduct? Imagine if the only people purged by the party had been those who criticized Nixon?

The decay of American democracy is real. It’s not a messaging or image problem. Until we can repair that, I’m not sure we can truly say America is back.

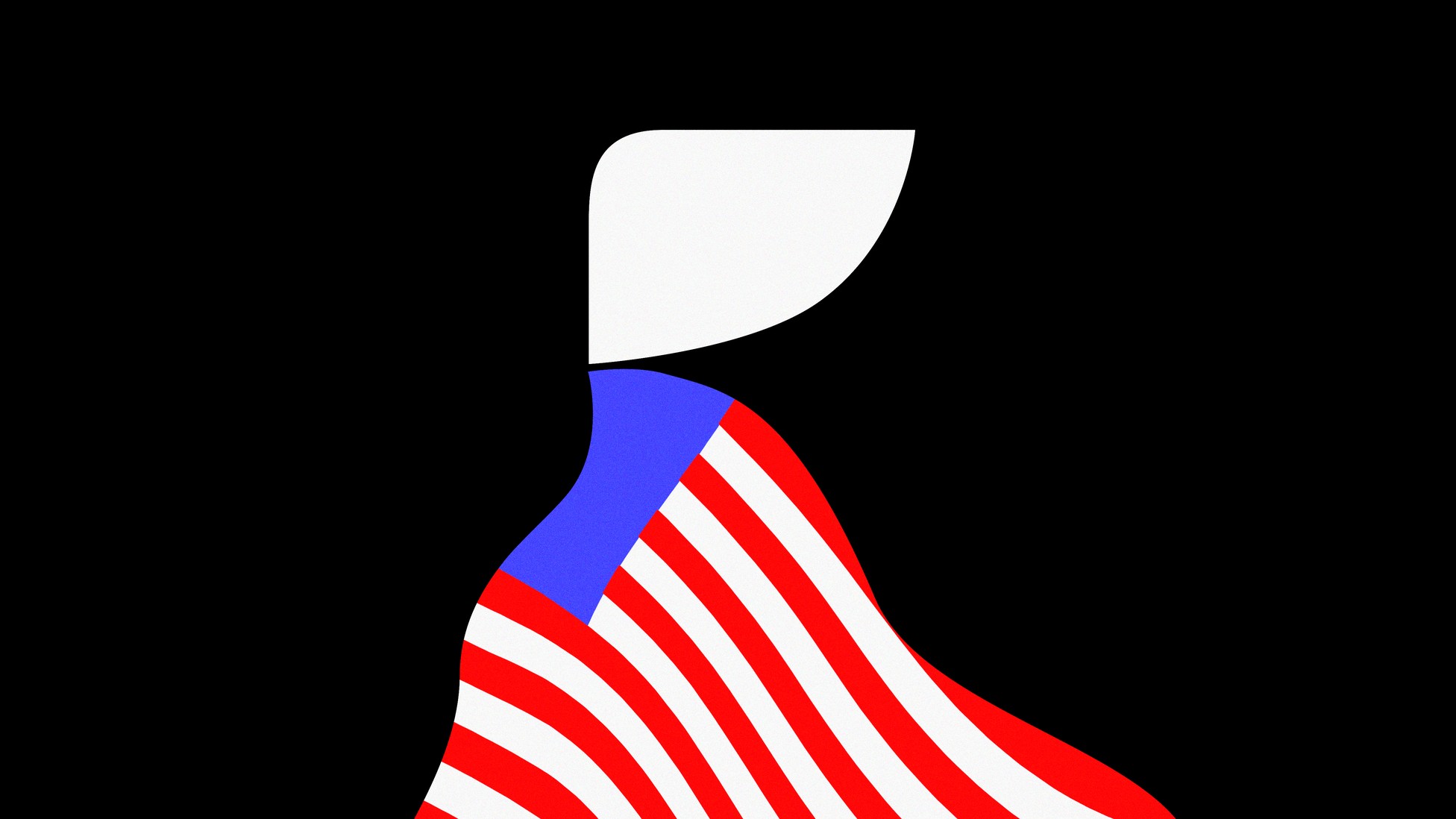

Along this line, a piece in The Atlantic looks at how democracy is eroding and what was once unthinkable is slowly being normalized much in the way that a slide toward dictatorship was shown in the book and TV show The Handmaiden's Tale. Frighteningly, too many people - perhaps out of shear exhaustion - think that with Trump out of office the threat is over. It is anything but over and people need to wake up before it is too late. Here are column excerpts:

When the TV version of The Handmaid’s Tale premiered in 2017, the show was a textbook piece of Trump-era resistance art—a direct reply to the preening misogynies of the newly elected president. Both the book and the show were timely parables of gendered violence, reminders that history can also move backwards. And they retain that power today: The Trump administration may have concluded, but its encroaching cruelties have not. State leaders are currently attempting to legislate away the rights of, among many others, trans people, of other LGBTQ people, of women. But The Handmaid’s Tale is urgent again for another reason as well. Lawmakers in several states, empowered by the nearly friction-free spread of Trump’s Big Lie, are attempting to limit people’s ability to vote—and building the power to cast as “fraudulent” those electoral outcomes they find politically inconvenient. They are doing much of this in a way that might be familiar to Atwood’s readers: They are treating these elemental threats to democracy as if they were business as usual.

“This may not seem ordinary to you now, but after a time, it will,” Aunt Lydia, whose job is to indoctrinate young women into the ways of Gilead, assures her charges. “It will become ordinary.” She means this as a promise, but in truth, it is a threat. Gilead, like many of the real-world regimes that inspired it, uses ordinariness as a tactic of oppression. Much of its propaganda is aimed not at angering people, but at soothing them. Its invented language is strategically casual. In this world, ritualized rapes are known as “ceremonies”; murders of dissidents are dismissed as “salvagings”; violence is made so routine that it becomes unremarkable. In a story full of villains, ordinariness is its own kind of enemy.

The regime that has conquered much of America in The Handmaid’s Tale takes advantage of the fact that, in times of crisis, people’s desire for normalcy can be so deep that it can easily edge over into complacency. “The new normal,” in this universe, is not a cliché. It is a concession.

“There was little that was truly original about Gilead,” the coda to the novel, a retrospective academic presentation about the workings of Gilead, observes. “Its genius was synthesis.” You might say something similar about the novel itself. It is powerful in part because its fictions flow from the hard facts of history: Atwood’s story blends lessons from Iran’s theocratic revolution, from Nazi propaganda, from the perfunctory playbook of 20th-century autocrats. But some of the book’s deepest insights are human-scaled. Atwood pays a lot of attention to the fact that Offred spends much of her time as a victim of Gilead merely … bored. “There’s time to spare,” Offred notes. “This is one of the things I wasn’t prepared for—the amount of unfilled time, the long parentheses of nothing.”

“Shocking but not surprising” was one of the truisms of the Trump era, a means of conveying how readily his aberrant—and often abhorrent—behavior had been normalized. Trump proved that shamelessness can work as a smoke screen. Other politicians have learned that lesson. Earlier this month, a group of democracy scholars produced a joint statement of concern about threats facing the American electoral system. As of this writing, nearly 200 experts have signed it. “We … have watched the recent deterioration of U.S. elections and liberal democracy with growing alarm,” they wrote. They cited in particular Republican-led efforts to pass laws that could enable some state legislatures or partisan election officials to do what they failed to do in 2020: reverse the outcome of a free and fair election. Further, these laws could entrench extended minority rule, violating the basic and longstanding democratic principle that parties that get the most votes should win elections.

Many of these affronts to election integrity are being enacted, in the name of preserving election integrity. They are extensions of Trump’s Big Lie. They are systematic. “We did it quickly and we did it quietly,” Jessica Anderson, the executive director of Heritage Action for America, a sister organization of the Heritage Foundation, told donors about voter-suppression measures that the Iowa legislature had passed in February. She described the template the firm had produced that served as a model for Iowa’s and other state-sponsored voting restrictions. The overall effort, she suggested, had been remarkably straightforward. “Honestly, nobody even noticed,” she said. “My team looked at each other and we’re like, ‘It can’t be that easy.’”

It can be that easy. It should not be that easy. One of the paradoxes of this moment of democratic emergency is that the threat, strictly speaking, doesn’t always look like the crisis it is. Laws being passed by lawmakers: This would seem to be business as usual. The whole thing is, for the most part, very orderly. Part of the challenge, for the public, will be to see the emergency for what it is—even if the encroachments are bureaucratic rather than outwardly violent, and even if the changes come slowly before they come suddenly. There are many ways to attempt a coup. And there are many ways for the unthinkable to become, finally, banal.

Be very afraid for the future.

No comments:

Post a Comment