Over a two-decade career in the white-collar think tank world, I’ve continually wondered: Why can’t we have nice things?

By “we,” I mean America at-large. As for “nice things,” I don’t picture self-driving cars, hovercraft backpacks or laundry that does itself. Instead, I mean the basic aspects of a high-functioning society: well-funded schools, reliable infrastructure, wages that keep workers out of poverty, or a comprehensive public health system equipped to handle pandemics — things that equally developed but less wealthy nations seem to have.

The anti-government stinginess of traditional conservatism, along with the fear of losing social status held by many white people, now broadly associated with Trumpism, have long been connected. Both have sapped American society’s strength for generations, causing a majority of white Americans to rally behind the draining of public resources and investments. Those very investments would provide white Americans — the largest group of the impoverished and uninsured — greater security, too: A new Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco study calculated that in 2019, the country’s output would have been $2.6 trillion greater if the gap between white men and everyone else were closed. And a 2020 report from analysts at Citigroup calculated that if America had adopted policies to close the Black-white economic gap 20 years ago, U.S. G.D.P would be an estimated $16 trillion higher.

To understand what stops us from uniting for our mutual benefit, I’ve spent the past three years traveling the country from California to Mississippi to Maine, visiting churches and worker centers and city halls, in search of on-the-ground answers.

In Montgomery, Ala., I walked the grounds of what was once a grand public pool, one of more than 2,000 such pools built in the early 20th century. However, much like the era’s government-backed suburban developments or G.I. Bill home loans, the pool was for whites only. Threatened with court action to integrate its pool in 1958, the town drained it instead, shuttering the entire parks and recreation department. Even after reopening the parks a decade later, they never rebuilt the pool. Towns from Ohio to Louisiana lashed out in similar ways.

The civil rights movement, which widened the circle of public beneficiaries and could have heralded a more moral, prosperous nation, wound up diminishing white people’s commitment to the very idea of public goods. In the late 1950s, over two-thirds of white Americans agreed with the now-radical idea that the government ought to guarantee a job for anyone who wants one and ensure a minimum standard of living for everyone in the country. White support for those ideas nose-dived from around 70 to 35 percent from 1960 to 1964, and has remained low ever since.

It’s no historical accident that this dip coincided with the 1963 March on Washington, when white Americans saw Black activists demanding the same economic guarantees, and when Democrats began to promise to extend government benefits across the color line. It’s also no accident that, to this day, no Democratic presidential candidate has won the white vote since the Democrat Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts.

Racial integration portended the end of America’s high-tax, high-investment growth strategy: Tax revenue peaked as a percentage of the economy in 1969 compared with the average O.E.C.D. country. Now, America’s per capita government spending is near the bottom among industrialized countries. Our roads, bridges and water systems get a D+ from the American Society of Civil Engineers. Unlike our peers, we don’t have high-speed rail, universal broadband, mandatory paid family leave or universal child care.

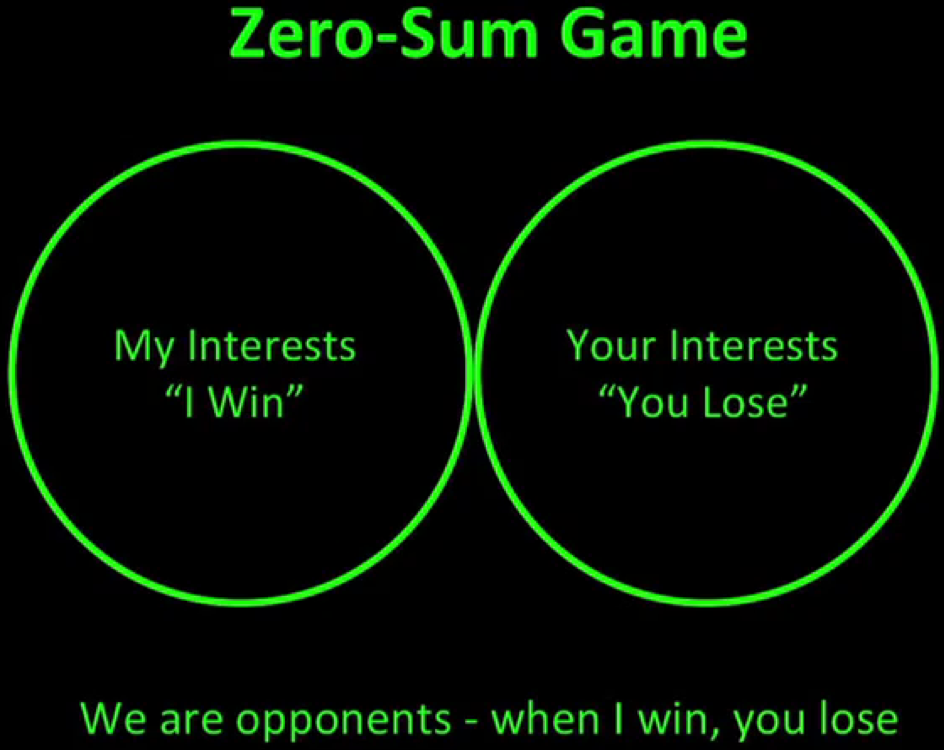

[R]acial resentment is the key uncredited actor in our economic backslide. White people who exhibit low racial resentment against Black people are 60 percentage points more likely to support increased government spending than are those with high racial resentment. At the base of this resentment is a zero-sum story: the default framework for conservative arguments, rife with references to “makers and takers,” “taxpayers and freeloaders.”

In my travels, I also realized that those seeking to repair America’s social divides can invoke this sort of zero-sum framing as well. Progressives often end up talking about race relations through a prism of competition — every advantage for whites, mirrored by a disadvantage for people of color.

In my research and writing on disparities, I learned to focus on how white people benefited from systemic racism: Their schools have more funding, they have less contact with the police, they have greater access to health care. These hallmarks of white privilege are not freedoms that racial justice activists want to take away from white people, however — they’re basic human rights and dignities that everyone should enjoy. And the right wing is eager to fill the gap when we don’t finish the sentence.

The task ahead, then, is to unwind this idea of a fixed quantity of prosperity and replace it with what I’ve come to call Solidarity Dividends: gains available to everyone when they unite across racial lines, in the form of higher wages, cleaner air and better-funded schools.

“In order for all of us to come up, it’s not a matter of me coming up and them staying down,” she said. “It’s the matter of: In order for me to come up, they have to come up too. Because honestly, as long as we’re divided, we’re conquered.”

This zero-sum mindset is so harmful to America yet too many cannot let go of it.

One thing fueling right wing white hysteria are the predictions that America is headed towards a minority-majority condition. Yet, as Sullivan's piece lays out, but for a "single drop" approach to racial classification, the whole picture morphs into something quite different and which might well be less terrifying to racists and white supremacists who cling to a zero-sum mindset. Here are excerpts:

If there’s one core assumption shared by the two tribes of our culture, it is that America will soon be a “majority-minority” nation. Among today’s seniors, “whites” still dominate; but among children, “non-whites” are now a very clear majority. The debate about when exactly America will become a majority-minority country moves around a bit in the projections, but it’s somewhere near the middle of this century. And this underlying reality has created a kind of background noise to our debates about race and culture, immigration and populism.

[I]t’s the simple, binary nature of this challenge that shapes our political divide: a “white” vs “non-white” America, “white people” vs “people of color”, “racists” vs “anti-racists”, “oppressors vs “oppressed”. It effectively makes America’s racial and cultural future zero-sum, in which we are currently neatly divided into two camps, and cannot all be winners. This Manichean vision shapes the woke left and the reactionary right, and it marches toward us.

Few have seriously debated or questioned this demographic orthodoxy (I include myself in this myopia). And yet it seems fundamental to our political present. In fact, I don’t think you can explain the persistence of Trump and Trumpism at all without understanding fears of a “non-white” future. And it’s hard to understand Democratic political strategy without appreciating their assumption that non-white immigrants will always be more reliable voters for them than white natives.

But what if this entire scenario is just empirically wrong? . . . Richard Alba, Professor of Sociology at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. His new book, “The Great Demographic Illusion,” examines and, I have to say, largely detonates, the majority-minority myth. He does this simply by pointing out how the Census Bureau actually defines “non-white”.

In a weird and creepy echo of the old “one-drop rule,” you are officially counted as “non-white” by the Census if your demographic background has any non-white component to it. So the great majority of Americans whose race is in any way ambiguous or mixed are counted as “non-white” even if they don’t identify as such.

What Alba examines is how these mixed-race populations understand themselves and behave within American society, and his conclusion is that our current situation resembles our assimilationist, melting point past much more than we currently believe. “In some fundamental ways,” Alba argues, “such as educational attainment, social affiliations, and marriage tendencies, the members of mixed groups appear closer to the white side of their background than to the minority side.”

This is particularly true with respect to the offspring of Latino-Anglo and Asian-Anglo couples, who are increasingly assimilated into the new bi-racial and multiracial mainstream. The only exception to this rule, alas, are black-white mixed children — who are more likely to be in single-parent homes, to be poorer and to have bad experiences with law enforcement, and thereby tend to identify with the non-white part of their identity. But even here, Alba notes, white-black children “not infrequently marry whites.” And the core difference between these kids and others is as much about class and family structure as it is about racism.

What Alba argues is that the “mainstream” to which many mixed-race Americans aspire is no longer best understood as a form of 1950s-style “whiteness” than as an inter-connected, 21st Century multicultural and multiracial kaleidoscope, in which many, especially the younger generation, feel increasingly at home. He wants to contrast the old “idea of assimilation as whitening” with “the ongoing mainstream diversification.” And if you do that, and complicate the white-non-white binary, the racial picture of America becomes much less fraught.

[W]hat of “Hispanic whites” — those whose lineage may come from South or Latin America in ethnicity but who also identify racially and socially as white? If you include them in this category, America remains two-thirds “white” all the way through 2060 and beyond. And this is not some wild diversion from previous definitions. Until 1930, Alba notes, Mexican immigrants were counted as “white” in the Census. If you kept that standard today, the whole notion of “majority-minority” would simply evaporate.

Insisting that biracial identity must always be categorized as non-white runs the risk of actually calcifying old doctrines of race, and fails to see the blurry lines of identity and assimilation that increasingly typify American life.

There is no reason, in other words, to believe that Latinos won’t be seen in 2060 the way Italian-Americans were seen in 1960, except that they will be assimilating into an off-white, brownish mainstream rather than a monolithically and stereotypically white one. More to the point, “the idea that US babies are now mostly minority is an illusion fostered by arbitrary classification systems — arbitrary at least with respect to the daily lives of these young children.” If these kids don’t define themselves in racially binary terms, why should we impose that anachronistic rubric upon them? And if they identify as white, why should we not take their word for it?

Inter-marriage is critical to this — and the rates keep going up. So many of the next generation will not have a clear racial identity to the naked eye, making the line between majority and minority increasingly moot.

Both pieces offer much to think about if one is a thinking person.

No comments:

Post a Comment